Central planning, however efficient it may seem to outsiders, always results in a tremendous misallocation of labor, capital, and resources. As a result, it invariably leads to economic stagnation and collapse.

Take China’s misadventures in steel, for example. The Chinese Communist Party has twice sought to dramatically increase steel production: first, during the Great Leap Forward, and second, under Jiang Zemin. The failure of the first is a matter of historical record. The failure of the second is unfolding in real time as you read this.

Both efforts can be laid to the perennial fantasy of Communist officials that they, as the vanguard of the proletariat, can manage an economy far better than the “counterrevolutionary” businessmen and entrepreneurs that they replaced.

Great Leap Famine

The most notorious failure of state planning in history—and certainly the most costly in terms of human lives—was China’s Great Leap Forward. It was launched with great fanfare in 1958, when Chairman Mao Zedong announced that China would mobilize the masses to overtake Great Britain in steel production within three years.Every commune in the country was ordered to construct backyard steel smelters. As the villagers scrounged for metal and wood to feed their furnaces, crops were left to rot in the fields. Food production plummeted and famine soon followed.

From 1960 to 1962, China went hungry, and an estimated 45 million people died of starvation. In the Guangdong production brigade where I did research from 1979 to 1980, some 200 people reportedly starved to death, mostly the very old and the very young.

If you thought this painful object lesson in the dangers of making grandiose economic plans would give China’s Communist leaders pause, you would be wrong. Mao’s successors have gone on to make precisely the same mistake, albeit at a slightly less breakneck pace.

Wasted Resources

In a slow-motion reprise of Mao’s earlier failed venture, a tremendous amount of capital, labor, and resources has been misallocated into steel production over the past 20 years.

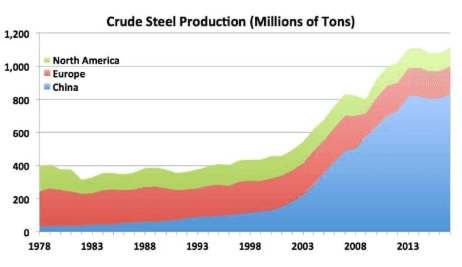

The chart shows China’s share of world steel production gradually increasing over the first 20 years of the “reform and opening.” By the year 2000, China was producing roughly 15 percent of the world’s steel, about what the United States was producing, and about what it required for its own consumption.

At that point, however, the geniuses who dictate economic policy in Beijing apparently decided that self-sufficiency in steel wasn’t enough. For strategic reasons—and perhaps also for reasons of national pride—they wanted absolute global dominance. And they were willing to heavily subsidize China’s steel industry to get it.

China’s major steel producers, such as Bohai Steel, are state-owned enterprises. So, it was a relatively simple matter to order them to ramp up production. But even smaller steel producers were offered low-interest rate loans, preferential tax rates, and hidden subsidies to get on board the Great Steel Train.

The result of the state’s massive investment in steel production was nothing short of astonishing. As the chart shows, China’s steel production shot up from 15 percent of global steel production in 2000 to almost 50 percent (49.2 percent) today. China now makes three times as much steel as Europe and North America combined.

To repeat: this increased production came about not as a rational economic response to market forces—the world wasn’t crying out for more steel—but as the result of a political decision by communist leaders.

Bankrupt Policy

The result of the Great Steel Train has been a persistent glut of steel on world markets, accompanied by accusations from a dozen countries that China was dumping steel at below the cost of production—which it clearly was. Trump’s 25 percent tariffs on imported steel, which was directed primarily at China, was precisely the right decision to level the playing field for U.S. steel manufacturers and workers in the face of China’s political actions.Steel companies, lured by government policies into massive and wasteful overproduction, now find themselves unable to pay back the loans that they were encouraged to take out. Some are going bankrupt, such as Dongbei Special Steel, which filed for bankruptcy in 2016 after Chairman Yang Hua committed suicide in March of that year, and Chongqing Iron and Steel, which went bankrupt in July 2017.

The most recent company to go under is Bohai Steel, once listed in the Fortune Global 500, which filed for bankruptcy in September 2018. Bohai filings report that the company’s debts total 192 billion RMB, but the actual amount of debt may be much higher. Few Chinese companies accurately report their debt levels, especially those that take the form of soft loans. In the case of Bohai Steel, according to professor Xiang Songzuo, the company’s real debt was probably closer to 280 billion RMB, much of which will never be paid back.

Mao’s backyard smelters ended up costing tens of millions of lives. Beijing’s more recent foolish venture into steel dominance will end up costing trillions of RMB, not to mention hundreds of thousands of jobs.

As China’s economy lurches into recession, the stream of sustaining government subsidies will necessarily dry up in province after province, and many more steel companies, undercapitalized and overleveraged, will go under. The contagion will spread.

The sad story of the rise (and incipient fall) of China’s modern steel industry is but one example of how the misallocation of scarce resources by state planners inevitably leads to ruin.

It’s a particularly poignant one, however, since this is the second time that Chinese Communist Party leaders have made exactly the same mistake.

And, as always, it is the longsuffering Chinese people who will pay the price for their utter economic incompetence.

Steven W. Mosher is the president of the Population Research Institute and the author of “Bully of Asia: Why China’s Dream is the New Threat to World Order.” Mosher, who is fluent in Chinese, was the first U.S. social scientist allowed to do research in China in 1979–80.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

Friends Read Free