Beijing is pushing hard for the quick execution of its RCEP free trade deal that will bind U.S. allies that signed up—including Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and the Philippines—ever closer to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

China, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam also ratified the agreement.

South Korea and the Philippines are two other close U.S. allies that signed the RCEP agreement, though they have not ratified it yet.

Ratifying a free trade agreement under duress due to a military threat, which is the state of Australia today, should make it void.

It is unclear to what extent the Academy modeled the loss of small and less competitive businesses in the Indo-Pacific due to greater competition from the region’s most powerful exporters, now unleashed in all RCEP markets.

It is also unlikely that the Academy included the effects of Beijing’s frequent use of trade as a political weapon against countries that insist on more transparency, for example, on the origins of COVID-19, or human rights and democracy in China. The effect of more money for Beijing’s mistreatment of Taiwan, Tibetans, Uyghurs, human rights activists and their lawyers, and the Falun Gong was likely not included in the analysis. Those intangibles invalidate any conclusion that empowering Beijing with more free trade is good for everybody. RCEP is not a Pareto improvement.

RCEP Is Risky

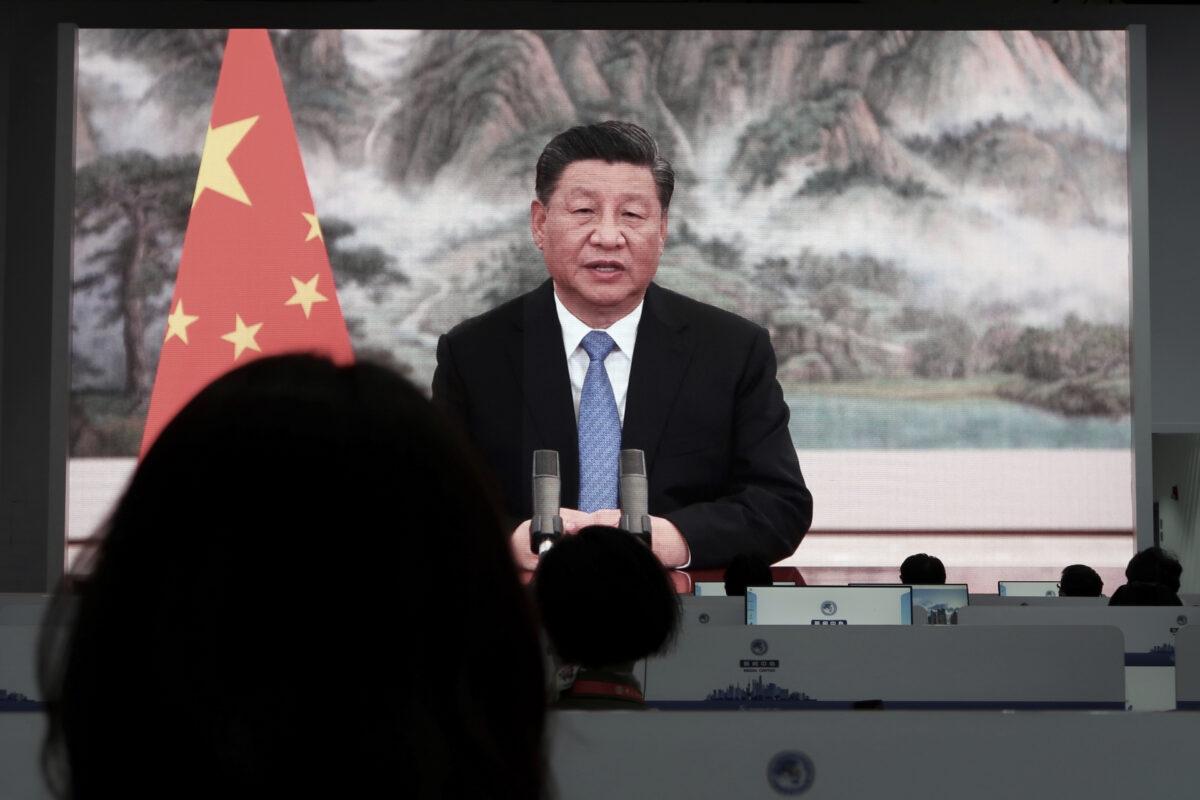

Once RCEP comes into force on Jan. 1, Beijing plans to rapidly reduce its tariffs, and will demand that other RCEP countries do the same. China’s General Administration of Customs “will maintain close communication with the customs of other member states to ensure the full implementation of the agreement’s rules of origin,” according to the Chinese ministry’s statement.Don’t expect perfect good faith on the part of the CCP. It excels at making promises and then innovating ways to get out of its obligations in the bargain, whether it be forcing political illiberality on Hong Kong despite its 1984 promise to Britain not to do so, or its attempted taking of the entire South China Sea, despite its promise in the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to honor other countries’ exclusive economic zones.

This indicates another major risk for RCEP countries: Beijing can use non-tariff barriers to protect China’s industries, while feeling entitled to insist on changes to local laws abroad to grease the skids for its exports. With RCEP, Beijing has a foot in your door.

Worse, RCEP is binding and could at some point be interpreted broadly by Beijing, which has a history of wild interpretations of international law and norms to fit its agenda of ever more power for the CCP. At some point, Beijing could attempt to transform the economic integration of RCEP countries into political integration—with the CCP in the lead. There are already clues along these lines in Beijing’s interpretation of RCEP.

This is how states and empires are built from previously independent polities and nations. The lead state uses incrementalism, cajoling, brinkmanship, and sometimes violence, to impose binding and “rationalized” forms of customs, standards, measures, laws, languages, and administrative procedures on subordinate states. This basic method of state-building was followed by emperors from Augustus in Rome during the 1st century B.C. to Charlemagne in France during the 8th century, and is now being used, in an obvious way, by the CCP in Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

RCEP Only Benefits China

According to China’s ministry, the “binding obligations involved in the agreement” include “simplification of customs procedures, product standards, service trade opening measures, investment negative list commitments, e-commerce, comprehensive intellectual property protection commitments, and administrative measures and procedures.”RCEP would be beneficial to Chinese companies that follow the party-directive to “go out” and engage in international trade, according to the Chinese ministry. RCEP “will increase the adoption of applicable international standards and use standards to provide a powerful force for Chinese manufacturing to ‘go global.’”

In China, the ministry organized “3 national RCEP special trainings, covering all prefecture-level cities, pilot free trade zones and national economic development zones. The number of participants in the training exceeded 66,000, and more than 70% were business representatives.”

Local authorities, customs, and industry associations conducted additional training, according to the ministry, making an additional “600 trainings of various types, with more than 100,000 participants.”

The ministry claims that RCEP, once implemented, will “promote regional economic integration and promote economic recovery and growth after the epidemic.” The ministry called RCEP a “major new development in East Asian regional economic integration.”

The CCP sees RCEP as a means of technology transfer as well. The ministry argues that the agreement will “increase economic and technical assistance to developing economies and the least developed economies to gradually bridge the development level differences among members, vigorously promote coordinated and balanced regional development, and promote the establishment of a new pattern of open regional economic integration.”

Beijing promotes its own economic growth through calling itself a developing or middle-income country and demanding special treatment, for example, at the World Trade Organization, World Bank, and during climate negotiations with developed countries. Wealthy countries, according to the CCP, should make costly transfers—in terms of carbon credits, subsidized loans, and technology—to the developing world, of which Beijing considers itself the leader and top beneficiary.

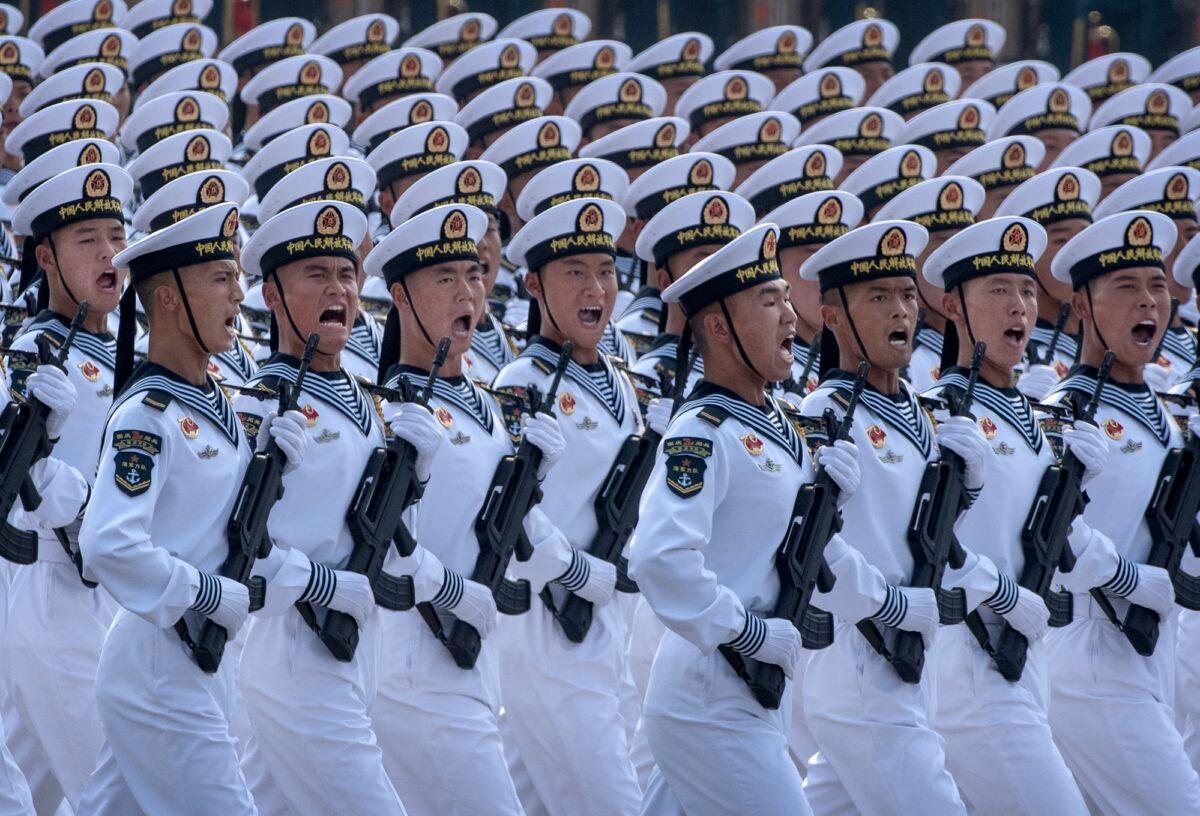

Ignore the fact that mainland China is still poor, according to international measures of per capita wealth, because of the failed communist economic policies imposed by the CCP. And ignore that Beijing takes full advantage of the resulting cheap labor of the Chinese people to profit on cheap exports to the world—profit that is used to build the Chinese military, that is in turn used to threaten the United States and its allies, including most notably Taiwan, with war.

Ignoring all that, American allies, such as Australia, are presenting RCEP as an unmitigated good. After RCEP takes effect, according to China’s ministry, “more than 90% of the goods trade between approved members will eventually achieve zero tariffs.”

The ministry argues that “With the implementation of rules of origin, customs procedures, inspection and quarantine, technical standards and other goods rules, tariff reductions and the abolition of non-tariff barriers will have a superimposed effect, significantly enhancing trade ties between members.”

Beijing’s larger economic system in Asia, through its imposition of RCEP rules, will be greater than the sum of its previously independent economic parts.

RCEP service trade agreements will cover finance, telecommunications, transportation, tourism, education, and more, according to the ministry. Strengthened investment protection will boost the mutual expansion of investment by enterprises from various countries in the region and, in particular, Chinese enterprises.

Dangers of RCEP

Where we should be decoupling with communist China due to its military aggression and human rights atrocities, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan are leading in the opposite direction.There is a danger that RCEP will be used for political purposes to bind countries and their domestic laws to China, even if at some point in the future they wish to break free. According to the ministry, RCEP will “strengthen the service functions of local governments” and “guide local governments to strictly implement domestic laws, regulations and rules that correspond to the mandatory obligations of the agreement.”

RCEP will “Accelerate the development of new formats and models of foreign trade, and cultivate new momentum for foreign trade development,” according to MOFCOM. “At the same time, local governments are encouraged to carry out precise investment in the industrial chain, and strengthen service guarantees for foreign-funded enterprises.”

RCEP clearly has a political element to it for Beijing. This is not just about trade.

According to the ministry, “The member states of RCEP jointly promote the agreement to enter into force as scheduled, and send strong signals against unilateralism and trade protectionism, support for free trade and the safeguarding of the multilateral trading system, which will further boost the confidence and determination of the member states to work together to achieve economic recovery after the epidemic.”

The MOFCOM statement continues, “After the RCEP is fully implemented, it will drive nearly one-third of the world’s economic volume to form a unified super-large-scale market. The space for development is extremely broad, and it will inject strong impetus into regional and even global economic growth.”

For Beijing, RCEP is particularly important for the penetration of foreign markets by Chinese business associations, in explicit support to Chinese businesses. The agreement will give “full play to the support and services provided by the Chinese foreign business organizations in the RCEP area to local Chinese-funded enterprises to make good use of the agreement,” according to MOFCOM.

“At the same time, RCEP gives full play to the role of major exhibition platform service companies such as China International Import Expo, China Import and Export Commodities Fair, China International Service Trade Fair, China International Investment and Trade Fair, China-ASEAN Expo and other major exhibition platform service companies to expand trade and investment to RCEP countries.”

Conclusion

RCEP is a powerful vehicle for China’s economic and political expansion into the 15 countries that signed the agreement, to the detriment of their small business community, and at the expense of not only their economic independence, but, increasingly, their political independence as well. At risk is Asia’s ethnic and political diversity, including the vulnerable democracies of Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand.The closer RCEP countries get to Beijing, the more their economic relations will be used to influence their capitals. Political leaders in democracies, who are often reliant on campaign donations for reelection, will be particularly vulnerable to the newly-strengthened special interests of exporters to RCEP in general, and to China in particular. Beijing will use that trade dependency for all it’s worth.

Friends Read Free