To boost returns and support a growing population of aging pensioners, China is embarking on a plan to centralize management of pension funds and divert more money into riskier asset classes.

The blueprint calls for transferring portions of local and regional pension funds to the centrally managed National Social Security Fund (NSSF), which is based in Beijing and has broader mandates to invest in riskier assets such as stocks, stock funds, and private equity.

The expansion of the NSSF and deployment of money into the stock market serves a dual purpose for the Chinese communist regime. In theory, investing in the stock market should generate greater returns and boost the size of the fund to cover growing pension commitments. This is something the local and regional funds couldn’t previously accomplish due to their investment restrictions and the low interest rate environment.

In addition, funneling more institutional money into China’s equity markets could reduce stock market volatility by decreasing influence of fickle retail investors. The more stable fund flow from pension funds should stabilize markets which has suffered from sudden retail investor inflow and outflows in the last two years.

Beijing began outlining a transfer of assets to the NSSF since last June, in the midst of Shanghai’s stock market bubble and subsequent crash. Guangdong Province was the first to transfer assets to the NSSF, and other provinces are following suit. As of December 2015, the NSSF managed 1.9 trillion yuan ($276 billion) of assets.

High Reward, Higher Risk

Currently, local and provincial pension funds are restricted to investing in safer asset classes such as bank debt and government bonds to preserve capital. But due to low interest rates, such investments have generated such meager returns that many pension funds find themselves unable to cover retirement payouts at a time when more state employees are approaching retirement.

The NSSF has no such restrictions and can invest up to 40 percent in stocks. At the end of 2015, 46 percent of NSSF’s assets were direct investments into companies, while the remainder were managed assets and investments, including stocks. According to the National Council for Social Security Fund which administers the NSSF, its assets appreciated 15.2 percent in 2015 and 8.8 percent inception-to-date.

Those are good returns, assume the figures are believable. But investment returns and monetary policy are often fleeting. Within a different set of circumstances—a higher interest rate environment, for example—the fixed-income heavy local and provincial pension funds could beat the returns of the riskier NSSF.

What this asset transfer from provincial funds to the NSSF means is that going forward, the fortunes of all Chinese state retirees now rest upon investment managers in Beijing.

The problem isn’t the disparate investment strategies between funds—competent investment managers can disagree on asset allocation philosophy. Pensioners should be concerned that the interests of NSSF investment managers in Beijing may not always align with those of the retirees.

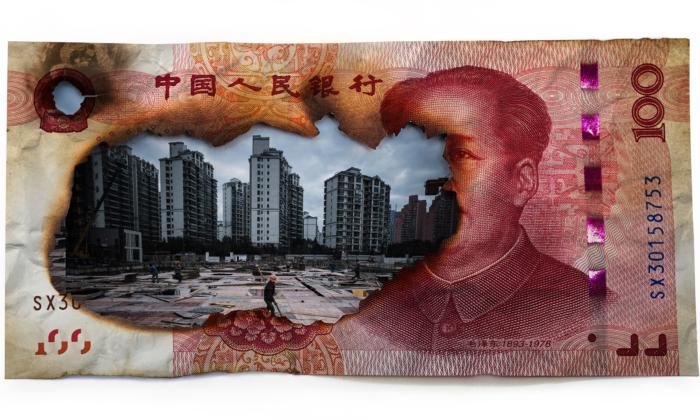

Exposure to Non-Performing Loans

The NSSF already appears to be doubling down on its risky bets by dipping into increasingly more toxic asset classes that could partially be motivated by political pressures.

The four massive state-owned asset management companies—set up to buy piles of non-performing loans (NPLs) from Chinese banks—are in the midst of raising new capital from a combination of IPOs and strategic investments from insurance companies and pension funds.

The NSSF will invest in at least two of these “bank banks,” as they’re commonly referred to—China Great Wall Asset Management and China Orient Asset Management. Both are also seeking IPOs early next year.

The bad banks were set up by China in 1999 to resolve the nation’s NPL problems resulting from years of bank loans to mismanaged state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The bad banks bought NPLs from state banks, freeing the latter’s balance sheets so they could keep lending to SOEs.

These bad banks essentially act as clearinghouses for China’s bad-debt problem. Beijing is able to shift such devalued—and sometimes worthless—assets away from the banks’ balance sheets, swapped out for either cash or bonds issued by the bad banks. That’s how the country’s big banks can claim sub-2 percent bad-loan ratios.

Initially, bad banks were given ten-year loans to finance the asset purchases and were supposed to go away after winding down the NPLs in ten years. But China’s debt-fueled economy has been generating so many NPLs that these bad banks are here to stay and need capital infusions to keep buying more NPLs.

And that’s where Beijing wants the NSSF and other retail investors to step in. Need more evidence that the interests of Beijing are going to increasingly influence management of pension assets? China’s recently deposed Finance Minister Lou Jiwei was appointed as the new chairman of NSSF, according to financial magazine Caixin.

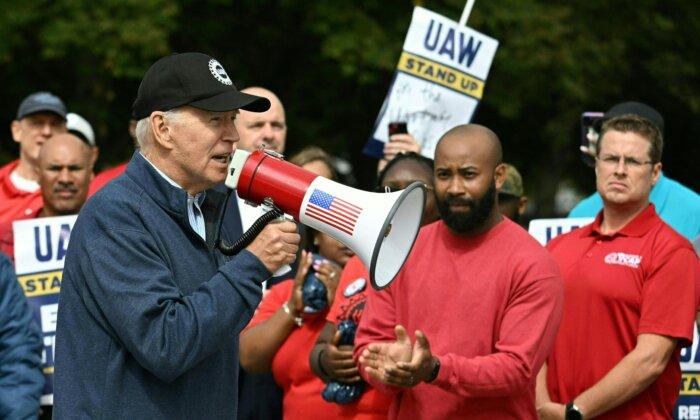

Early Retirement and Social Unrest

At the same time, some Chinese provinces are instituting early retirement plans to push workers off active state payrolls. At least seven provinces—mostly in the Northeast—announced the plans, in part to comply with Beijing’s directive last year to reduce steel and mining capacity.

Similar to the 1990s policy enacted by then-Prime Minister Zhu Rongji, these early retirees don’t count toward official unemployment statistics and their pension benefits are deferred. China’s official retirement age for state employees is 60 for men and either 55 or 50 for women depending on position. Early retirement plans generally accelerate those rules by five years. They get a reduced monthly stipend during the five years, but must wait until the formal retirement age to enjoy pension benefits.

This alone has generated a spate of small but growing protests in the nation’s rust belt. If NSSF’s returns falter and the fund has trouble meeting its liability payments in the future, Beijing’s problems could quickly exacerbate.

Friends Read Free