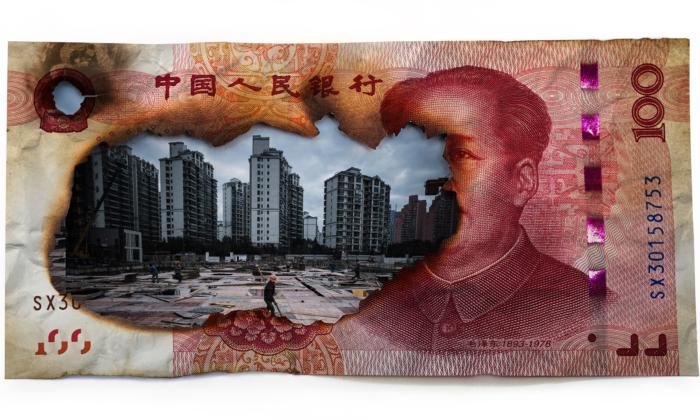

Foreign companies doing business in China have been waiting years for clarity from the Chinese communist regime on how they can extract their data out of China.

They’re finally getting what they were waiting for. But it hardly clarifies everything, and actually introduces new landmines.

This clarification has been hotly anticipated, as Beijing mandates that companies must undergo a series of data security “assessments” before they can transmit the data they own beyond China’s borders, to their headquarters, for instance.

It does clear up a few things. First of all, the agency overseeing this data is the CAC, China’s internet watchdog. The rules also dictate what types of companies must apply for assessment, how to apply, the CAC’s general assessment framework, and penalties for failure to obtain permission.

The rules also cover all data leaving China’s “borders,” which undoubtedly in this case means Hong Kong. So foreign companies doing business in Hong Kong also will need to be vigilant. It was previously a question as to whether Hong Kong was under the scope of this law, but legal experts have widely confirmed that Hong Kong is squarely within China’s boundaries for this purpose.

But aside from these general guidelines, the rules are unclear in many respects. The CAC states that all businesses processing data obtained in China must conduct periodic self-reviews and assessments of risks of transferring data abroad, and the firms in scope include “information infrastructure” companies and “key data” owners.

Companies gathering data from more than 100,000 residents or companies harboring “sensitive” personal information of 10,000 residents or more must undergo an approval process by the CAC before data can be transmitted.

The CAC said it would take 45 to 60 days on average and it would take into consideration the necessity of such transfers, the sensitivity of the data, and risks of loss should such data be compromised.

Who qualifies as “key data” owners, and what qualifies as “sensitive” personal information? That’s still unclear.

But such vague language would grant the CAC and the Xi Jinping regime with broad powers to restrict and punish companies. There also is considerable leeway to politicize such data without prior warning. Despite companies having to undergo self-assessment, the CAC is the judge.

Most foreign companies collecting data—any form of data—on their Chinese customers should plan conservatively and assume their data is sensitive unless told otherwise. Consumer, technology, financial, and health care companies would most likely be affected.

But it gets even more complicated.

These rules dovetail with China’s new Personal Information Privacy Law (PIPL), which went into effect on Nov. 1. Similar to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which went live in 2018, China’s PIPL carries heavy penalties for transgressors and has extraterritorial impact. Companies, including foreign companies with no presence in China but that have Chinese customers, could face stiff penalties if they are found to be in violation of the law.

China’s PIPL is even more strict than Europe’s GDPR in that the GDPR doesn’t limit transfers, and that the European guidelines stipulate that governments can’t obtain such data at will without subpoenas or warrants.

The Chinese laws grant no such protections for companies. Both the PIPL and the data extradition rules leave enough gray areas within their definitions for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to interpret and enact restrictions and penalties without limit.

Foreign companies interfacing with Chinese customers now face even more business risk than before.

Friends Read Free