News Analysis

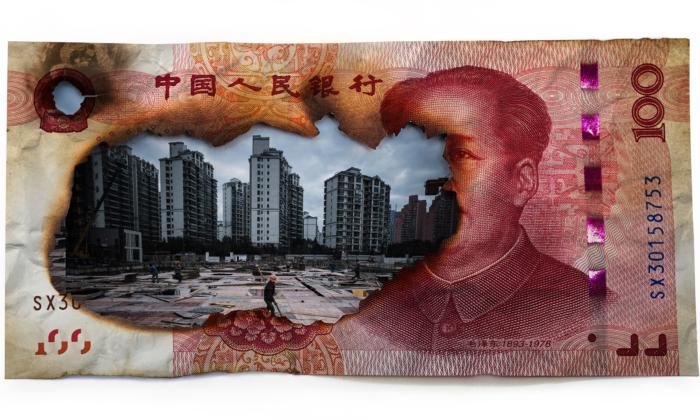

As part of China’s ambitious goal to wean itself off coal, China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. has announced plans to sell half its stake in a major cross-country natural gas pipeline, in a bid to raise capital and to fund exploration.

Sinopec, as the company is commonly known, is looking to divest 50 percent of the trans-China pipeline, which connects gas fields in the western province of Sichuan to cities on the eastern seaboard. In a filing with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on Aug. 2, the state-owned natural gas giant did not specify a timeline or a targeted valuation for the sale.

Despite declining profits and a global natural gas glut, the asset sale will fund new projects in shale gas extraction as Sinopec looks to meet the ambitious target of doubling its gas production within five years. China is betting big on a shale gas boom to decrease its dependency on coal and foreign gas imports.

So far, Sinopec has invested 62.6 billion yuan ($9.4 billion) to build the Sichuan-Shanghai gas pipeline. The 1,700-kilometer project began operations in 2010 and transports up to 12 billion cubic meters of gas per year.

Hong Kong brokerage CLSA believes the pipeline could raise 20 billion yuan ($3 billion) for Sinopec.

Global Gas Glut

China’s natural gas consumption grew at a rate of 3.3 percent last year, its slowest pace in 17 years, according to government data. That’s a far cry from the average annual growth rate of 15 percent between 2009 and 2014.

The global decline in gas prices—somewhat correlated with oil prices, which have faced similar challenges since 2014—has not generated stronger demand.

“We see massive quantities of LNG (liquid natural gas) exports coming online while, despite lower gas prices, demand continues to soften in traditional markets,” said Fatih Birol, executive director of International Energy Agency (IEA), in June. “These contradictory trends will both impact trade and keep spot gas prices under pressure.”

In its latest annual five-year forecast, the IEA sees global demand rising by 1.5 percent per year by 2021, 50 basis points lower than last year’s forecast.

Cheap coal, low oil prices, and weak global economic growth are several headwinds that have dampened natural gas demand and created excess inventories.

Despite obvious challenges, China is doubling down.

Both Sinopec and China National Petroleum Corp. (PetroChina) are pushing ahead with billions of dollars’ worth of new investments in natural gas exploration and extraction, especially from shale formations.

According to data from PetroChina, in 2015 China used around 200 billion cubic meters of gas, a quarter of which was imported. China has bold plans to decrease reliance on foreign gas imports as well as replace a portion of its coal consumption with domestic natural gas. Its latest Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) called for the replacement of coal use in all non-power generation sectors.

Shale Boom Dreams

With a global supply glut and China’s mandate to increase domestic shale production, Chinese gas imports could slow, which prompted some analysts and media to sound the alarm on foreign gas producers.

But not so fast.

On paper, China has huge shale reserves. But digging deeper, it’s difficult to envision China realizing its own shale boom any time soon.

The industry is dominated by three major state-owned entities: Sinopec, PetroChina, and CNOOC. These companies have invested around $15 billion in U.S. shale companies to access fracking technology, aiming to bring the know-how to China and create a fracking boom there.

By its very nature, hydraulic fracturing (fracking) is a high-cost production. The process involves injecting high pressure water and chemicals to create fractures in deep rock formations and release natural gas and petroleum.

In the United States, critics have condemned fracking’s environmental impact on water quality and links to increased seismic activity. An “environmental tax” is implicit in U.S. drillers’ high costs—drillers typically pay 15 percent royalties to the land owner, plus local and state government taxes.

It’s even more challenging for China. Its shale gas deposits lie far deeper underground and in more complex geological formations than, for example, the U.S. deposits in the flatlands of North Dakota and Texas, which drove much of the recent American growth.

Experts estimate that Chinese gas wells would require almost twice the amount of water to crack open than what is required at U.S. shale sites. That’s a tall order for a country facing annual droughts, with “less water per capita than Namibia or Swaziland, where land twice the size of New York City turns to desert every year,” according to Mother Jones magazine.

The challenges don’t stop there. Besides the high production costs, China’s shale resources are unevenly distributed. It does not have a single giant gas field; its various sites are remote from the demand centers on the nation’s eastern and southern coasts.

A lack of infrastructure, an underdeveloped pipeline network, and the limited projection capabilities of service industries mean that even after extraction, Chinese gas companies face high delivery costs. These challenges could cripple domestic producers’ ability to compete with foreign producers.

The shale developments will further erode Chinese energy companies’ bottom line, which has already been squeezed by falling oil prices. Sinopec’s net income fell 30 percent last year to 32 billion yuan ($5 billion). Its larger rival PetroChina’s net income fell 66 percent from $19.2 billion in 2014 to $6.5 billion last year.

Beijing’s policy on natural gas has been to keep prices low for consumers to the detriment of producers. That puts even more pressure on gas companies to lower their production costs.

On the ground, the drilling continues. A Wall Street Journal reporter visited Sinopec’s shale drilling site in Fuling District, near the city of Chongqing in Sichuan Province. The reporter was barred from interviewing local villagers about the impact of the drilling, but the plant manager disclosed that Sinopec gave a 1 percent stake to a local government entity to help curry favors from local politicians.

With the controversy of fracking and China’s heightened level of social unrest serving as a backdrop, China’s blueprint for a new shale gas boom simply doesn’t inspire confidence.

Friends Read Free