Financial markets usually take a shorter term view and focus on things like quarterly economic growth, the exchange rate, as well as capital flows—especially when it comes to China recently.

Every once in a while, it’s good to focus on some longer term indicators, which will shape the economy for the next decades, like population growth and the availability of workers.

Case in point: Every year the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) in China puts out a report analyzing the status of migrant workers and just released the one for 2015.

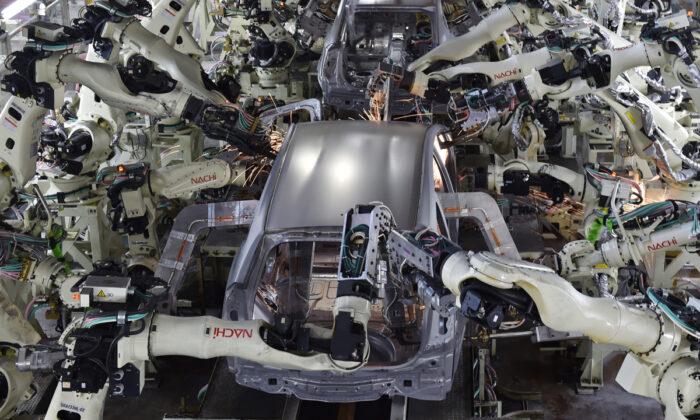

Because migrant workers usually work without formal contracts and in very economically sensitive segments like construction and manufacturing, changes in wages and employment provide a good snapshot of where the overall job situation and economy are right now.

Longer-term trends in worker migration describe the potential for the economy to increase productivity per worker, as they move from lower value-added jobs like farming in the countryside to higher value-added jobs in the city. This was big in China over the last 20 years.

Chinese migrant workers make up 277 million or one-third of China’s workforce. Some of them actually don’t move from their home province and just work in different jobs from agriculture in their home provinces. They are still classified as migrants because of China’s hukou registration system. Some of them move to another province in China to try their luck to build a better future.

For the short-term, the report confirms that the Chinese economy is getting worse, as other on-the-ground surveys confirmed throughout 2015 and the first quarter of 2016.

Wage growth slowed from 9.9 percent in 2014 to 5.6 percent in 2015 on average, with manufacturing and construction showing the biggest declines.

The number of workers not paid on time increased to 2.8 million during that period, the bulk of them coming from those two sectors. On average, they will have to do without three months’ pay for the foreseeable future.

For the long-term view, the trend of migration from the countryside to the cities, which contributed to China’s fast economic growth for the last 20 years is probably over.

“There are major demographic shifts underway, including that the working age population has peaked,” research firm Capital Economics writes in a note to clients.

The net increase in migrant workers peaked in 2010 at around 12 million; last year they only increased by 3.5 million. According to Capital Economics and other researchers, China has reached the Lewis Turning point—the move from the countryside to cities is over.

The Chinese regime wants to increase the number of people with urban hukou to 45 percent by 2020 from around 35 percent in 2014. It may succeed because of a bureaucratic trick.

“The government has been granting more urban hukous to migrant workers since 2010. Once migrants have an urban hukou they are reclassified as urban workers and removed from the migrant data,” Capital Economics states.

This is positive for the statistic, but does not change the economic reality on the ground, as only migrants who already live in the cities can get the urban hukou.

The population still left in the countryside is staying put as the wages for agricultural work have risen and the country faces shortages of important food items, such as pork.

“The pool of surplus workers in the countryside has now all but dried up. Rural wages are rising rapidly making it harder to entice them to go elsewhere,” writes Capital Economics.

Urban Benefit

Consulting firm McKinsey, however, is going against the grain and suggests Chinese consumers aged 15-59 and living in cities will increase by 100 million by 2030.

“By 2030, the number of consumers in this segment will grow by 20 percent. ... Their average per capita consumption is expected to more than double from $4,800 per person annually to $10,700. By 2030, this group will spend 12 cents of every $1 of worldwide urban consumption,” McKinsey states in its Urban World Global Consumer Report without saying how it obtained the data or its estimates.

According to the chart below, McKinsey expects the population aged 15-59 to keep growing in most urban areas in China.

The projection comes despite the fact that this age group declined by almost 5 million in the whole of China in 2015 according to official data, and other institutions like the World Bank, expect the working age population to decline another 10 percent by 2040.

Friends Read Free