In a trip to his former northeastern stomping ground this April, the Chinese regime’s second-in-command, Li Keqiang, bemoaned the sorry state of the stagnant industrial region.

“I used to work in the northeast and can be considered half northeasterner, so I don’t have to be too polite,” he said in a talk to officials in Changchun, the capital of northeast China’s Jilin Province, according to state media. “Your [economic] statistics indeed make me worry.”

As for “incompetent and lazy officials,” Li suggested that the Party “strike hard, publicly expose them, and resolutely criticize them!”

But the plight of the northeast—a land home to over 100 million people and the size of Great Britain, France, and Germany combined—is not just a matter of local concern. They are systemic ills, brought about by the weaknesses of Party control that plague China as a whole, such as corruption, economic inefficiency, and demographic decline.

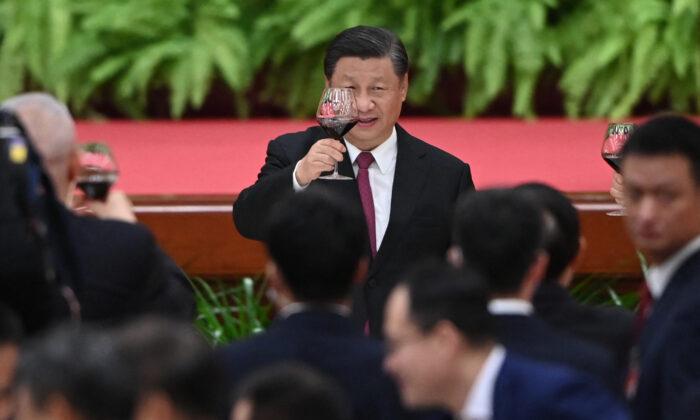

Soon after Li’s visit, Communist Party head Xi Jinping gave a speech calling for the revitalization of the region’s struggling economy at another Communist Party meeting in Changchun, Jilin Province.

Xi’s words echo the rhetoric of a decade-old campaign to bring the provinces of the northeast—Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Liaoning; in the past known as Manchuria—up to speed. In the last generation, the industrialized, historically tumultuous land of punishing Siberian winters and near-tropical summers has missed out on much of the meteoric development enjoyed by the prosperous coastal parts of China.

It’s not for want of resources or capital. Manchuria, with its fertile soil, was for many years an important breadbasket. It is blessed with abundant mineral resources, including oil, coal, and iron. In the early 20th century and during World War II, it was coveted by Japanese militarists, who saw it as their empire’s “lifeline” and the jewel of their conquests. Japanese planners ordered the construction of a vast complex of railways, mines, and factories, often through cheap or forced Chinese labor.

Under Chairman Mao, Manchuria retained its role in heavy manufacturing and resource extraction. Today, the northeast remains shackled to an all-too-Soviet economic structure that much of China has left behind.

An Economic Nightmare With Soviet Characteristics

In the 1990s, as China experienced accelerated economic growth, what set Manchuria apart from the rest of the country was its untypically high level of existing industrialization, making it more comparable to a former Soviet country such as Russia or Ukraine. In these nations, formerly Party-controlled enterprises, now run by oligarchs, fueled rapid growth of institutional corruption and social decay.

Following Japan’s surrender in 1945, Manchuria was liberated and returned to China. When the Communist Party took over the former colony and then the rest of China, it inherited the fruits of Japanese management and local labor. Under Soviet tutelage, Mao created massive state-owned enterprises to run China’s command economy, and Manchuria became the heartland of a centrally planned military–industrial complex.

Chinese administrators and economists replicated the practices of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin and created a system geared primarily for the seizure and maintenance of communist political and social control in favor of economic efficiency or sustainability.

The Stalinist economic structure was implemented across China as a means of securing the Communist Party’s totalitarian “legitimacy in society and of primacy in industrial management,” as Deborah A. Kaple describes in the book “Dream of a Red Factory.”

“The leitmotif of all Chinese Communist writings of this period, like the Soviet postwar literature, was the justification of Communist Party control and power in the enterprise,” Kaple wrote.

Even after Mao’s death and the rise of the market economy, however, the heavy hand of the Party is still present in the state-owned enterprises and banks that dominate China’s economic landscape.

‘Revitalizing’ a Deadlocked System

When Premier Li Keqiang visited in April, he heaped scathing criticism upon local officials, saying that they were living off of “free meals” provided to them by the public instead of working diligently. But altering bureaucratic incentives will take time—and require more than mere remonstrations from Li Keqiang, blunt as they were.

In the downsizing of the 1990s, Manchuria suffered heavy unemployment as factory workers were laid off en masse. The result was significant worker unrest involving tens of thousands of laborers who went on strike and would block rail traffic shipping northeastern industrial goods and raw minerals to the rest of China.

Twelve years after the Party launched a campaign to revitalize the old industrial base of northeast China by expanding the private, service-oriented sector, the corruption-and-inefficiency-prone heavy regime-controlled industries are still king. And productivity has dropped, reflecting the overall dip in the investment-driven real estate and infrastructure markets.

In the late 2000s, following a 4 trillion yuan stimulus package that allowed for continued nationwide investment in a bloated real estate and infrastructure sector, Manchurian manufacturing became valuable again, but the problem of economic diversification was never resolved.

Regional demographics have been especially hard-hit by the unintended effects of the regime’s one-child policy and in light of an increasingly noncompetitive state-run industrial and resource extraction sector.

According to China’s 2010 national census, the northeast has a birthrate of about one child per woman, far below the national average of 1.5, and less than half the natural replacement rate of 2.1. By comparison, Japanese women have an average of 1.34 children, according to 2013 data. South Korea, another nation known for severe population decline, had a total fertility rate of 1.19.

Around 2 million people leave Manchuria every year, mostly to find work in other parts of China, according to mainland Chinese media Caijing, citing a study by Peking University. The population is also aging, with only 11.8 percent of northeasterners under 14 in 2010, according to the census of that year.

As the overall Chinese economy suffers from a real estate bubble that has stopped driving growth, the auto industry, once the pride of the northeast, has also slumped.

According to Charles Freeman III, international principal at the Forbes-Tate public policy consulting firm, the devolution of power from the Party central to local authorities (a measure to implement growth during the early years of China’s economic reform) had its side effects.

Giving local officials authority in economic development also gave them the opportunity to enrich themselves. In an interview with Quartz, Simon Powell, head of oil and gas in Asia for brokerage CSLA, said that the collusion of third-party companies with state-run giants opened up “almost boundless” avenues for “corruption and nepotism.”

“The rent seeking for a long time was working quite well for driving economic growth, but clearly it’s become a drag on growth and Party legitimacy,” Freeman said in a telephone interview.

“The incentive structure for a lot of bureaucrats in China, and a lot of their power and prestige, has come because they’re at the front end of licensing and decision making,” Freeman said. “To change to a post facto government structure, a lot of those incentives, whether they’re aligned with corruption or other rent seeking, will have to be removed.”

Friends Read Free