News Analysis

Beijing’s plan to turn China into a global soccer powerhouse has led to several investments in foreign clubs over the past year, despite China’s general controls on capital exiting the country.

With official state backing, Chinese foreign investment into soccer clubs ballooned over the past year. Over ten deals were closed since early 2015 involving clubs in the U.K., France, Italy, and Spain.

The latest deal was announced last week, when a group of unidentified Chinese investors bought A.C. Milan, a participant in Serie A and one of the most successful European clubs in history, from former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. The purchase valued Milan at around $500 million.

The A.C. Milan deal comes merely a month after Chinese retailer Suning Holdings purchased a 70 percent controlling stake for around $300 million in Internazionale, another club in Italy’s Serie A.

In the same month, on June 17, Chinese businessmen Chien Lee, Zheng Nanyan, and a consortium of other investors acquired an 80 percent stake in French Ligue 1 soccer club OGC Nice for an undisclosed sum.

China’s shopping spree over the last year has netted the country a list of Who’s Who of European soccer clubs, including varying stakes in Spanish club Atletico Madrid, English Premier League teams Aston Villa and Manchester City, France’s FC Sochaux-Montbeliard, Czech’s Slavia Prague, and others. The Chinese funding came from a spectrum of sources, including individual businesspeople such as Wang Jianlin, private companies, and state-owned companies such as Citic Capital.

Uncertain Financial Returns

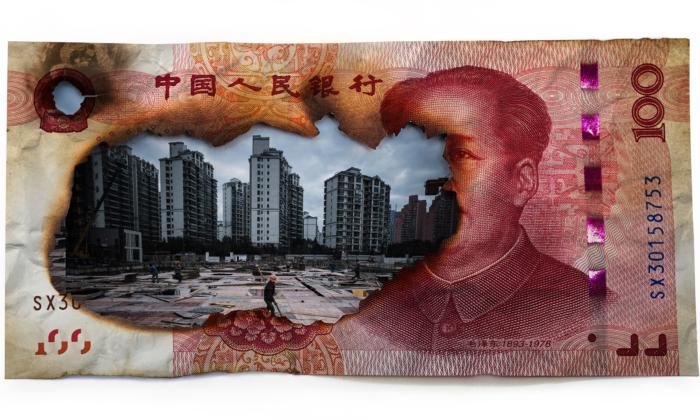

Depreciation pressure over the yuan has led to rising demand for foreign assets. But as an investment, soccer clubs have traditionally yielded mediocre results.

Soccer clubs in France’s Ligue 1 and Italy’s Serie A both recorded aggregate operating losses for the 2014-2015 year, according to data from Deloitte’s Annual Review of Football Finance 2016.

Even the Premier League—which is consistently one of the most lucrative—have seen its profitability shrink last year compared to the year before, although as a whole the league has improved their finances from the decade leading up to 2013 when most clubs were deeply in the red due to wage inflation. The ratio of wages to revenues were 61 percent in the 2014-2015 period, 3 percentage points higher than the prior year, Deloitte noted.

Profits at some of the most successful clubs are often razor thin, as a result of wage inflation and high debt service cost. Arsenal, for instance, recorded a pre-tax profit of only 3.8 million pounds ($5 million) in 2014, while Manchester City had losses of 17.7 million pounds ($23 million), according to analysis from U.K.’s Daily Mail.

With currency volatility surrounding the pound and the euro and downbeat economic climate in the Eurozone, outlook for soccer club profitability is uncertain at best.

For a more tangible comparison, we can look to the stock market. The STOXX Europe Football Index, which tracks public share performance of listed European soccer clubs, has fallen 27.4 percent over the past 5 years. That’s a dismal performance compared to the 45.2 percent gain recorded over the same period for the benchmark STOXX Europe 600 Index.

Playing Sport or Politics?

It’s no secret that Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping is personally a fan of soccer.

China’s State Council issued sports industry reform and development edicts in 2014 that likely became the impetus for recent Chinese investment in soccer both domestically and abroad. In a similar policy document issued March 2015, Beijing called for making China a soccer powerhouse by 2050.

To boost the country’s global standing in soccer, Beijing has set out to build up to 20,000 soccer schools around the country within the next five years, following the success of Evergrande International Football School in Guangdong Province, one of the world’s biggest soccer academies. This summer, Chinese soccer clubs also made headlines by paying huge sums in the transfer market for foreign talent.

As with most business decisions from Chinese organizations, politics is often as important as financial returns. And it’s no different for China’s recent thirst for foreign soccer teams.

Lee and Zheng—new owners of OGC Nice—cited last month “strategic and financial reasons” for their purchase of the French soccer club. Peter Schloss of CastleHill Partners, a Beijing-based sports and media agent consultancy, told Chinese business journal Caixin that Chinese companies investing in foreign soccer clubs often gain from “political and business aspects.”

What type of strategic and political gains can be gained?

For high ranking Chinese business leaders, investing in soccer—both foreign and domestic—is another way to curry favor with China’s leader. Since 2012, Xi has embarked on an “anti-corruption” campaign that has investigated and removed from office scores of senior party and business leaders.

A business leader or company promoting soccer is a show of solidarity with Xi and helps to execute his vision for China as a regional soccer leader.

Perhaps more importantly than personal reasons, exerting control over major institutions in the world’s No. 1 sport has other benefits for the ruling party.

China is keenly aware of the power of arts and culture—and soccer is the world’s dominant sport culture in terms of global reach. Beijing’s control over popular foreign soccer clubs, and by extension its players, is one more way for the party to deploy “soft power” globally, indirectly promoting China’s foreign policies, mollifying the problematic aspects of its international image, and expanding its PR influence.

It’s more evidence that for China, political returns could prove just as valuable as monetary returns.

Friends Read Free