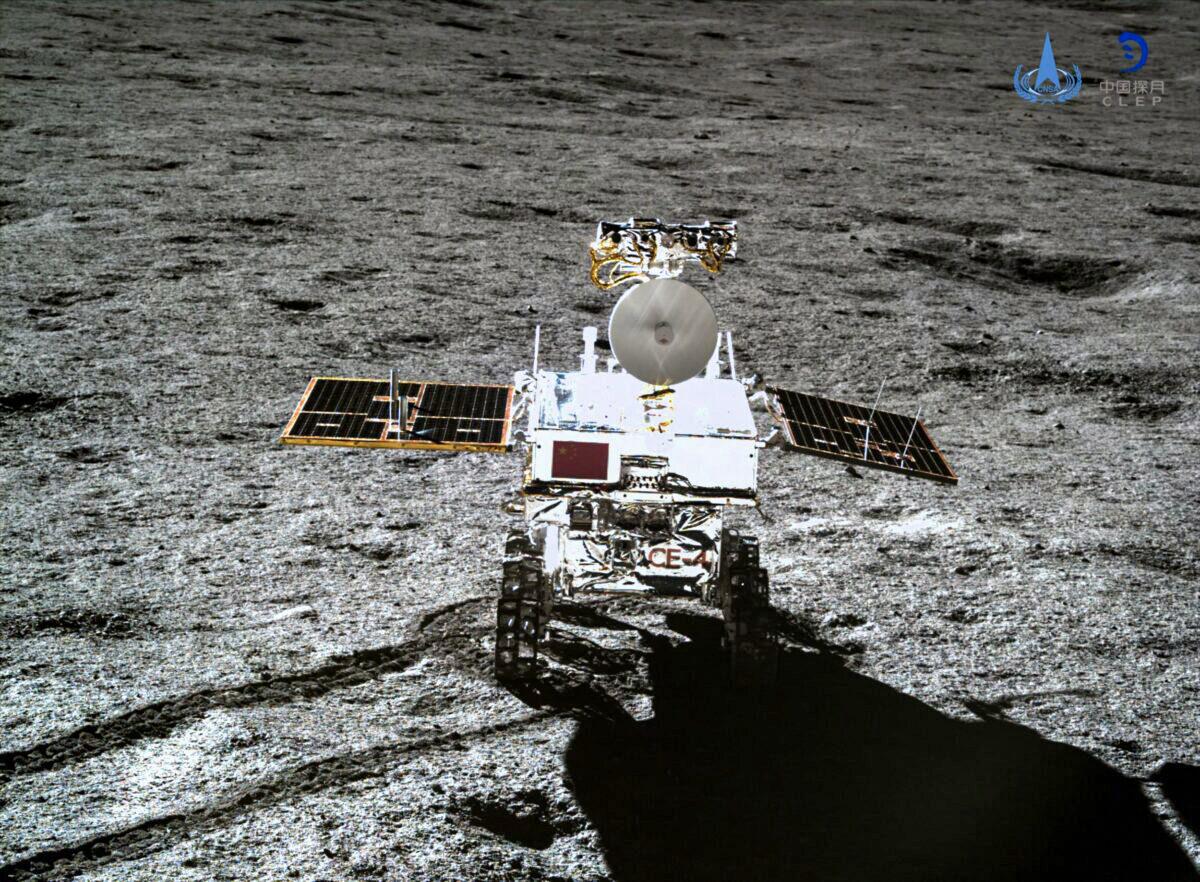

It appears that a 2022 agreement between China and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to have a 15-pound moon rover hitch a ride on the 2026 Chinese Chang-e-7 unmanned probe to the moon has reportedly been canceled following objections from the United States that it may violate U.S. International Traffic In Arms Regulations (ITAR).

While the cancellation has not been confirmed yet by any public announcement from China or the UAE, it was unofficially announced on March 24 in the South China Morning Post (SCMP), a Hong-Kong based newspaper owned by Alibaba Group.

The UAE is also an original 2020 signatory to the U.S.-led Artemis Accords, in which 23 nations now pledge “to commit to seek to refrain from any intentional actions that may create harmful interference with each other’s use of outer space in their activities under these Accords.”

China’s manned space program, including its unmanned and manned moon and Mars programs, is controlled under the Strategic Support Force (SSF) of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

These linear relationships justify concern that Beijing will place military capabilities on the moon and may seek to control access to and from that body as part of larger ambitions to control the Earth-moon system, and to better enforce eventual military hegemony on Earth.

The CCP’s intention to militarize its presence on the moon was signaled in a recent article in the Number 3, 2022 volume of China’s Journal of Deep Space Exploration, titled “Current Status and Prospect of Lunar-based Earth Observation Research.”

The article was written by Guo Huadong with the Beijing-based International Research Center for Big Data for Sustainable Development, Ding Yixing of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Digital Earth, Aerospace Information Innovation Research Institute, and Liu Guang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences University in Beijing.

The authors note that for 50 years, Earth observation from space has been carried out by various platforms. They claim that “no single platform can solve all space Earth observation problems. It is necessary to explore the advantages of different platforms to form a complete Earth observation system to solve this problem. The moon is the closest extraterrestrial body to us, and it is also the only planet that humans have landed on. It provides us with a unique place to observe the Earth.”

The authors list scientific objectives that could be assisted by lunar-based Earth observation, such as monitoring the Earth’s climate, monitoring the macroscopic land movement on Earth, and lunar observation, which could even assist the monitoring of distant stars in determining if their exoplanets can support life.

But without saying so specifically, the authors also describe a clear civil-military “dual use” that would benefit the military objectives of the PLA—detecting “targets” in the cis-lunar space between the Earth and the moon.

They note, “Detecting, tracking, identifying, and cataloging space objects such as small natural celestial bodies and man-made spacecraft can help improve the safety of man-made spacecraft, and can also provide timely warnings of catastrophic events such as planetary impacts.”

The authors add: “Since there is almost no atmosphere on the surface of the moon, the transmission loss of the moon-based space target monitoring system is small, and there is no atmospheric window limitation, so the band selection is more flexible. The microgravity on the surface of the moon makes it easier to design and install various large-caliber telescopes and antennas, thus effectively improving the ability to monitor space targets.”

Regarding the best sites on the moon for observing the Earth, the authors note that the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has listed Sinus Iridum, Mare Nectaris, and Shackleton.

Shackleton is on the south pole of the moon, and both China and the United States have identified it as a potential early candidate for unmanned and manned lunar landings.

However, using the moon for Earth observation is not enough. Earth observation should also be conducted from the Lagrangian points, locations of equal gravitational pull around the Earth that would ease the placement of unmanned satellites or manned space stations.

The article states: “Extend the concept of moon-based Earth observation to lunar orbit, orbit around the moon, and Earth-moon Lagrangian point observation. The Earth-moon Lagrangian point can form a full-coverage observation network for the Earth with the moon base, and can also form a long baseline formation flight, thereby enriching the mission chain.”

This article illustrates how China’s communist regime intends to deploy dual-use military capabilities to the moon—under the guise of peaceful exploration.

Using radar, optical, and digital sensors to find “targets” between the Earth and the moon means they will also be assisting the SSF in its mission to find and destroy U.S. deep space early warning satellites critical to the U.S. ability to sustain nuclear deterrence.

Identifying the Shackleton site as having potential military value means that the CCP may seek to contest control of this area with the United States and other countries; it warns others that Beijing could view this area as “territory.”

In addition, the article’s suggestion that Earth observation systems be deployed to the Lagrangian points to supplement observation from the moon clearly indicates that China seeks greater control over the Earth-moon system and that it eventually wants to control access within and then beyond to Mars.

This article is the latest indication that Beijing’s intentions for the moon are inconsistent with the Artemis Accords. Its signatories should avoid cooperation with the Chinese regime in space until it agrees to transparency and a system of assurances that prove that they are.

Friends Read Free