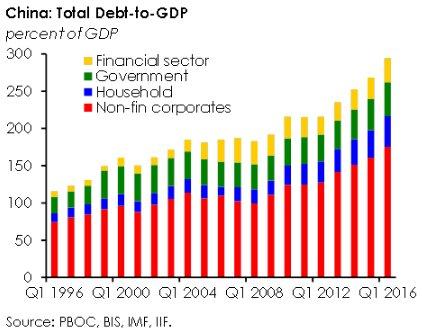

By now most people have realized that China is, one, addicted to debt and, two, its debt addiction is not sustainable.

Any country investing around 50 percent of GDP in infrastructure and productive assets over a decade or so will run into overcapacity problems. Overcapacity simply means there is infrastructure and factories to make things, but nobody is consuming them.

No, or not enough consumption means no cash flow and if the projects are debt-financed this creates a payment problem.

China fans—until recently—have brushed this argument aside saying that the country is growing very fast and will one day be able to use this infrastructure. Furthermore, the totalitarian communist regime could always bail out everybody.

There are still some people who believe China will escape its 300-350 percent debt to GDP load and decreasing debt efficiency without much of a crisis.

This optimistic scenario is unlikely to happen according to Société Générale’s chief China economist Wei Yao. She thinks China has to restructure one way or another and presents some more realistic albeit unpleasant outcomes.

“It is impossible to avoid deterioration in the efficiency of credit allocation with the pace of debt growth that China has seen. In our view, the reason that China has so far avoided a banking crisis is because it remains a relatively closed system,” writes Yao.

SOE SOS

The main problem, according to Yao, are the State Owned Enterprises (SOEs), which have the most debt (127 percent debt to GDP), worst profitability (3.4 percent of GDP), and worst return on assets (smaller than 2 percent). More than a quarter of the industrial SOEs are consistently loss-making.

Given their track record, Société Générale estimates about 18 percent of SOE debt could go bad, leading to total losses of around $800 billion. Losses to the Chinese banking system because state banks own most of SOE loans and bonds.

The Communist Party ultimately controls the whole banking system either outright or through the state organs. And it’s CCP officials who benefit most from corruption. “The bankers, whose primary allegiance is to the Party rather than to their institutions, still have little choice but to support local government projects,” Mark DeWeaver wrote in his book “Animal Spirits With Chinese Characteristics.”

So Société Générale thinks that“all in all, SOE debt restructuring could jeopardize 50 percent or more of the banks’ capital base, which—if it materializes quickly—would almost certainly knock China’s banking sector into a systemic crisis.”

While these words may sound shocking to the uninitiated, it is nothing we haven’t seen before. China had to bail out SOEs and banks in the late 1990s when 30 to 50 percent of all debt went bad.

So bailing out the SOEs will also involve bailing out the banks as well. Nobody likes bail-outs, but Société Générale has some suggestions how to minimize the damage.

First, the so-called “zombie companies” should be closed down systematically and the debt written off. Given the magnitude of the bad loans, however, the banks cannot shoulder that cost alone, a cost which is going to be higher than just the bad SOE debt.

Because of some knock on effects and some private sector problems, “total losses in the banking sector could reach $1.2 trillion, equivalent to more than 60 percent of commercial banks’ capital, 50 percent of fiscal revenues and 12 percent of GDP.”

Restructuring Options

In the late 1990s, the government completely bailed out the SOEs and the banks, but this is unlikely to happen again.

“Previously, the government—also the sole shareholder of China’s banking sector at the time—picked up the lion’s share of the bill, and it received significant help from solid economic growth in the 2000s. This time, not only will that same split be hard to achieve—and it should not be replicated—but future economic growth will not be as helpful either,” writes Yao.

Aside from forcing banks to exchange bad debt for an equity stake in the troubled company, which is a short-term fix, banks will have to use up their existing capital base and also raise new money from private investors.

The central government would then issue new bonds (currently only 15 percent of debt to GDP are in the form of government bonds) to the tune of 10 percent of GDP.

“The new [bond] supply would be equivalent to 3-9 percent of GDP, 12-35 percent of fiscal revenues and 20-60 percent of outstanding [bonds]. In addition to bank recapitalization, the government would have to provide fiscal support to address unemployment pain and other social effects. The total fiscal bill would probably be considerably more than 10 percent of GDP.”

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) could play a role by either doing Quantitative Easing (QE) and buying up some of the bond supply or by using up its foreign exchange reserves to make up for the banking losses. It would have to because the Chinese bond market is not liquid enough to just double in size within the space of a year or so.

Both options are not without problems, however, as QE would put further pressure on the already brittle currency whereas the selling of foreign exchange reserves would put deflationary pressure on the already deflating manufacturing economy.

In the best case scenario, those two factors could offset each other.

“The bottom line is that the government bail-out program could be designed in a way to greatly limit its impacts on currency and capital account stability. Such designs seem to exist in theory, but would be very difficult to realize in the real world,” writes Yao.

At the end, China may just choose to reform everything from zombie SOEs to state banks to letting the currency free-float and opening the capital account. They might as well, while they are at it, although may not be pretty according to Yao.

“Given the immense challenges and risks inherent in the debt restructuring, it is unrealistic to expect a perfectly smooth process.”

Friends Read Free