The People’s Republic of China’s new system for acquiring organs—and the man behind it, former Vice Minister of Health Huang Jiefu—has been lauded in some circles as a decisive break from the use of executed prisoners as organ sources. But critics regard the new arrangements as implicitly coercive, and argue that the lack of transparency allows organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience and others to continue.

Most would agree that any system is better than one that relies on killing prisoners of conscience, or death row inmates, as the primary organ source.

The secret about the new system, however—its heavy reliance on cash payments, sometimes large ones, to secure organs from the Chinese rural poor—is only mentioned quietly in the official literature, and experts say it runs the danger of contravening one of the World Health Organization’s guiding principles for organ transplantations.

There is a vigorous debate in the community of medical ethicists about the role of financial compensation in voluntary organ donations: directly paying people tens of thousands of dollars for a kidney is called organ trafficking. But reimbursing “reasonable and verifiable expenses” incurred by the donor is OK, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

China’s new system appears to sit outside the WHO’s guidelines, however, since officials refer to payments of up to several years the wages for an average rural resident.

Arne Schwarz, an independent researcher of organ trafficking based in Switzerland, wrote in an email, “Whatever these payments are called—financial incentives, compensation, aid or humanitarian assistance—basically organs of deceased people are bought with money and other material advantages. This is the legalization of a new kind of organ trafficking.”

He pointed to the definition given in The Asian Task Force on Organ Trafficking, which described financial incentives as a type of coercion.

Several Years’ Income

The new Chinese system, it appears, did not start out with the goal of paying for organs. A pilot program was run from March 2010 to March 2012, led by the Red Cross Society of China; but it convinced only 207 people to donate. Of course, the Red Cross in China does not have the reputation it holds in other countries. It is not independent of the communist regime, and its credibility took a punishing blow after a corruption scandal in 2011.

Seeing the flagging uptake in donations, the authorities began offering payments to the families of Chinese peasants—“the rural poor,” as they are described in reports—for the organs of recently deceased family members, and a modest uptick in donations followed.

It is often difficult to get clear, coherent, and complete information about the progress of these programs from official Chinese sources. Researchers, like Schwarz, who have subjected the system to careful analysis, have to assemble a mosaic piece by piece by reading volumes of state media reports.

A throwaway line at the end of an unrelated article this year in China Daily, for example, notes: “As of March 31, over 719 people had donated their organs, of which 1,964 were major organs, such as hearts and kidneys, saving the lives of over 1,000 patients.”

That was the authorities’ admission that after the financial compensation was implemented, 500 new participants signed up within the space of a year, when in the previous two years only over 200 had taken part, underscoring the role of payouts in the new scheme.

A piece by Qiang Fang of the College of Medicine at Zhejiang University, published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, went to great pains to explain how the financial compensation offered in China was within ethically appropriate bounds—that it was more compensation for expenses incurred rather than large payouts.

The characteristic lack of transparency in the operations of the system, however, makes it hard to know whether the cases referred to by Qiang are typical or not.

In other reports, Chinese officials speak less guardedly about the amounts on offer.

Gao Xiang, the vice executive of the Red Cross Society of China Zhejiang Province, referred to cases of 34,000 yuan (US$5,500) payouts (including funeral expenses); the article said, “Financial assistance paid to the families of donors does not exceed 50,000 (US$8,000) yuan.”

Gao continued: “It’s very limited. But it shows the humanitarian spirit of the Red Cross.”

Given that the average rural income in China is around 7,000 yuan, or around US$1,100, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, a payment of as much as seven times annual income could have the effect of altering incentives in the decision-making process for family and doctors, according to analysts.

Black Box

If the system runs by “going to a financially vulnerable cohort” and offering them large sums of money, “you’ve decided that coercion is the way out of the situation,” says Maria Fiatarone Singh, a professor of medicine at the University of Sydney. “Most people think it’s not appropriate to offer large sums of money to people who are vulnerable.”

Another issue that goes to the heart of the credibility of the new arrangements relates to how they are situated within the broader political and institutional framework in China under the rule of the Communist Party.

For over a decade the Party engaged in the harvesting of criminals for their organs, and then relied heavily on the labor camp population of prisoners of conscience, predominantly Falun Gong practitioners, according to researchers, who believe the practice continues.

There is still no real information disclosure on the current composition of organ transplants in China—no death penalty statistics, for example, which would be a useful proxy for figuring out minimum and maximum possible transplantation numbers from that source.

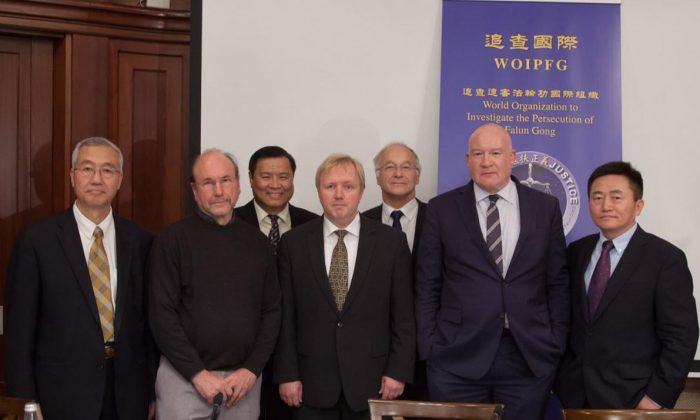

The black-box nature of the system as a whole, which the compensated donation scheme is slotting into, resolves few of the concerns expressed by David Matas, a Canadian lawyer who has researched extensively the harvesting of organs from Falun Gong practitioners.

“It’s impossible to have an ethical system in isolation from the rest of the organ sourcing system, which is not ethical,” Matas said in a telephone interview. “Without access to information, judicial review, human rights reporting, and media reporting, the mechanisms that allow you to find out what’s going on simply do not exist, and the prospects for their existing are not there as long as the Communist Party maintains its rule.”

In those circumstances, he said, “there is no way the system will meet the need for transparency, accountability, and traceability” per international standards.

Dr. Torsten Trey, the executive director of the medical advocacy group Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting, said that as long as the system is not open to international scrutiny, prisoners of conscience could still easily be targeted as organ sources.

Noting the facility with which hospitals can produce fraudulent documents in China, he said: “If it’s so easy to provide a fake identity to ‘transplant tourists,’ then it is also possible to give fake identities to detained prisoners of conscience.”

Friends Read Free