The good news first: China’s trade surplus rose to $59.5 billion in May from $34.1 billion in April.

The bad news, it comes entirely from a drop in imports (-17.6 percent compared to a year ago), which means the Chinese economy is grinding to a complete standstill.

“Our estimate suggests that quarterly annualized growth averaged 6 percent just this decade, below 5 percent for 2014. For the first quarter, we calculate a contraction. Real domestic demand collapsed by nearly 8 percent annualized compared to the last quarter of 2014,” said Diana Choyleva of Lombard Street Research.

If the trade surplus had been achieved by rising exports it really would have been good news, but that’s not the case. Exports also dropped 2.5 percent compared to May of 2014, although they did rebound from April of this year.

What these data points really mean is that two drivers of China’s growth are completely disintegrating.

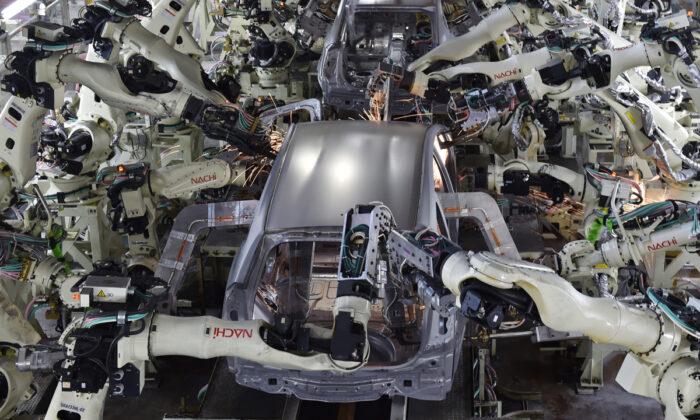

Exports and foreign direct investment have been responsible for around 50 percent of Chinese growth during the past decade, according to Yuqing Xing and Manisha Pradhananga of Tokyo’s National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies.

“Based on these results, we conclude that the Chinese economy remains highly dependent on external demand in the form of exports and FDI, and rebalancing the economy toward domestic demand has not been achieved yet,” they wrote.

The problem now is that exports have gradually become less competitive because of higher labor costs and a relatively stronger currency.

The other half of growth comes from investment in mostly real estate and production capacity for which you need lots of raw materials. Imported raw materials.

Because this investment was funded by a lot of debt and many projects are currently not returning enough cash flow, this model has also been scaled down. If China is not building any more ghost cities and excess production capacity, it doesn’t need to import a lot of raw materials, hence the drop.

Friends Read Free