China is going to “thoroughly implement” a long-discussed real name registration system on the Internet in 2015, signaling the latest attempt by the authorities to further rein in the free-flowing medium that so often makes the regime the butt of its jokes.

Forcing Chinese Internet users to register their activity online through their real names will have the effect of further limiting the already confined space for speech online, analysts say. The policy was announced by the State Internet Information Office on Jan. 13, and conveyed widely to the public through state media.

The idea has been tossed around in the halls of power in China for over two years. Authorities said that requiring major Internet platforms to register the real names and identification numbers of users will prevent unspecified “Internet crimes.”

But regular Chinese see it as a much more sinister move: an attempt to limit their freedom to criticize the government online, and to stop them from spreading information and news that the regime wishes to censor.

The State Internet Information Office said that initially only instant messaging platforms will implement the real name system—these include microblogs like Weibo (which is similar to Twitter), online forums, electronic bulletin boards, and a number of other websites. The office vowed to “intensify supervision, management, and enforcement” of the policy.

Another initial goal of the authorities is to have 80 percent of users of the ubiquitous instant messaging application WeChat—they pointed it out as an example—registered with their real names and identification information by the end of the year.

Those who don’t register users, or who publish “untruthful information,” or information about gambling, fraud, pornography, and so on, will have their websites shut down, the Internet Office said. Over 50 such offending websites have been shut down since the clampdown began.

The enforcement of the real name system has been criticized harshly in China by activists and regular Internet users—they worry that the regime will simply use the information it forcefully collects to take revenge on Internet users who write things the authorities don’t like.

Chinese rights lawyer Liu Xiaoyuan said the real name system will have the direct effect of quelling speech online. “What we’ve seen is mostly restraining rights. There’s no unified standard for what can be said and what can’t. If the authorities think you shouldn’t have said this or that, they can arrest you,” Liu said in an interview with New Tang Dynasty Television.

The Chinese online celebrity Wu Bin, known online as “Xiucai Jianghu,” told Radio Free Asia that the intensified restriction on speech will eventually lead to some kind of outburst from the public.

“The government keeps blocking speech, and one day resistance will flood out. I deeply feel the increasingly tightened freedom of speech—my Sina Weibo account is blocked every few days. The government is only losing people’s hearts. In the short term it can control speech, but long term it’s accelerating its own destruction,” Wu said.

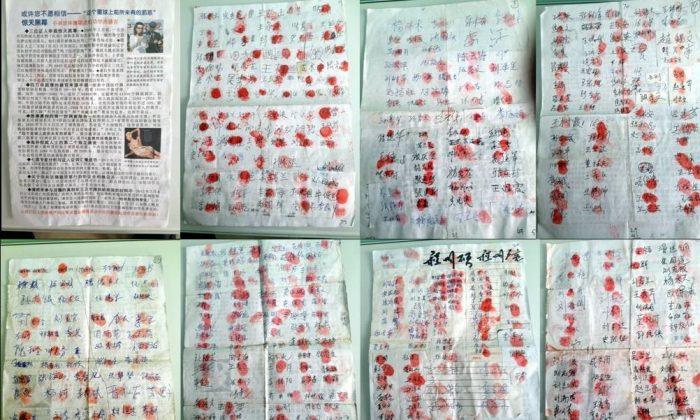

Chinese security services have carried out mass arrests or summonses of Chinese deemed activists or dissidents this year, and many others have been put under house arrest. Communist authorities have strictly blocked information about the occupation of streets in Hong Kong by the city’s pro-democracy youth, and last year nearly 80 people in mainland China were detained for supporting genuine universal suffrage in the region, according to Amnesty International. Many of those arrested had done nothing more than post comments online supporting the movement, or convey photos and other information about it.

In Guangdong Province alone, which borders Hong Kong, at least nine citizens were arrested and charged with “inciting subversion of state power” because they spoke out in favor of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy demonstrators.

Freedom House, based in Washington, D.C., last year ranked China as the third worst country in Internet freedom, from 65 countries across six regions—the only two worse were Iran and Syria.

With additional research by Li Xinru

Friends Read Free