While the United States and China are upping the ante in their ongoing trade dispute, so far the effects on the Chinese economy and financial markets have been far more pronounced than on the United States.

China said on Aug. 3 that it would impose new tariffs on $60 billion worth of U.S. imports after President Donald Trump threatened to increase the tariff rate on Chinese imports earlier in the week.

The new tariffs would be placed on U.S.-made aircraft and liquefied natural gas (LNG)—an important fossil fuel that China tried to keep off the hit list as long as possible—in retaliation for Trump’s most recent proposal to boost the rate of threatened tariffs to 25 percent from 10 percent.

Dialing up the pressure on China wasn’t entirely unexpected, as Trump earlier this month eased up in his trade skirmish with Europe in order to double down on his China efforts.

“What was unpopular was a tariff war against the world. The administration realized that and shifted gears,” Dennis Wilder, a China adviser to former President George W. Bush, told the Financial Times on Aug. 3.

A Natural Gas Gamble

On paper, China’s threat of reducing LNG imports from the United States could be detrimental for the U.S. energy industry, and, potentially, Trump’s business supporters in key regions.Several companies have plans to ramp up investments in LNG production and export, especially in southern states such as Texas and Louisiana. Cheniere Energy announced on May 22 that it would build a third plant, in addition to two existing projects under construction in Texas. This was in anticipation of a 25-year LNG export deal signed in February with state-owned China National Petroleum.

China is the world’s second-biggest LNG importer and the third-biggest destination for U.S. LNG exports. Any long-term disruption in U.S. LNG exports, theoretically, could have negative consequences for Trump and the Republican Party’s midterm election prospects.

But it also has an effect on Chinese consumers. LNG is Beijing’s alternative fuel of choice to replace the country’s coal addiction.

“American gas doesn’t come with a ‘Made in America’ label on the molecules,” Charif Souki, co-founder of Tellurian Inc., which is developing the Driftwood LNG terminal in Louisiana, told S&P Platts. “This will not affect the trade but will simply make gas more expensive to Chinese consumers.”

Curiously, around the same time as the announcement of the potential tariff escalation, China said that it is developing more capacity to take in higher LNG imports. The Ministry of Transportation plans to build 11 new LNG terminals in northern China to increase capacity to handle future LNG imports, according to Caixin Global, a Beijing-based business magazine.

Trump is well aware of this. The United States is deploying a calculated gamble in hopes of wrapping up the trade dispute well before the elections. In fact, China’s decision to potentially increase taxes on LNG imports—a strategically important resource for China—is a signal that Beijing is running out of options and inching closer to tapping out.

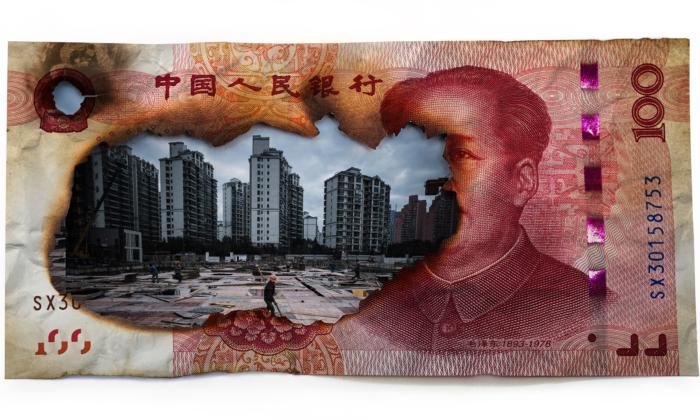

Pressure is mounting inside China. Its stock market has been one of the world’s worst-performing major markets in 2018. The benchmark Shanghai Composite Index fell by 1 percent on Aug. 3, the third straight period of decline. Over the past six months, the index has fallen by 21.4 percent.

“China’s stock markets have made people lose so much money over the past few years, and investors have lost their faith,” Kingston Lin King-ham, of Hong Kong-based securities brokerage AMTD, said in an Aug. 3 South China Morning Post report.

One day earlier, China lost its ranking as the world’s second-largest stock market. According to Bloomberg, the total value of Chinese equities was a combined $6.09 trillion, just shy of the $6.17 trillion value of Japanese stocks.

Politburo and Central Bank Stepping In

China’s once-booming economy has been reeling this year due to a confluence of factors; The ongoing trade war has simply added fuel to the fire. The private Caixin-Markit China manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) fell to 50.8 in July, the lowest level in eight months. China’s official PMI reading also fell in July.Growth in China’s services sector also is slowing, as Caixin-Markit’s PMI on the sector fell to 52.8 in July, a four-month low.

On July 31, China’s Politburo—the Communist Party’s governing committee—gave hints that the tariff war is having a negative impact on its economic growth outlook.

“Today’s quarterly Politburo economic meeting highlighted increased external challenges and pledged to meet 2018 economic targets,” Morgan Stanley economist Robin Xing wrote in a note to clients July 31.

“It plans to implement prudent monetary policy, while maintaining proactive fiscal policy to support domestic demand (particularly infrastructure capex).”

The yuan has been in a freefall as the trade war has ramped up. Last week marked the eighth consecutive week that the currency depreciated against the U.S. dollar.

The People’s Bank of China released a statement late Aug. 3 that it would raise banks’ risk reserve ratio requirement from zero to 20 percent on foreign exchange (FX) forwards they execute for clients. This rule makes it a more expensive bet against the yuan and to exchange yuan into foreign currencies.

The central bank first imposed a risk reserve on FX in late 2015—also in an attempt to halt the yuan’s depreciation—but removed the requirement in September 2017.

Friends Read Free