When Margaret McCuaig-Johnston first began speaking out against the Chinese communist regime’s human rights abuses, the former senior government official had been “a friend of China for 40 years” and had “helped them develop their innovation capacity.”

Today, she says “Canadians should speak truth to power every time they meet with Chinese officials.”

Organized by the University of Ottawa, where McCuaig-Johnston is a senior fellow with the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs and with the Institute of Science, Society and Policy, the conference was focused on “protecting human rights and democracy in the global institutions of the 21st century.”

McCuaig-Johnston had a 37-year career in government during which time she held senior management positions and for seven years was a member of the Canada-China Joint Committee on Science and Technology.

She said she first took an interest in China in 1978 when she was a civil servant in the Ontario government. The country was in the midst of its first democracy movement, opening up after isolating from the outside world for decades and having launched various political campaigns that killed millions of its people.

Wei’s essay on the wall was soon joined by other posts put up by workers’ groups and students in protest over political and social issues in China.

McCuaig-Johnston, who with her husband went to China to “see the wall for ourselves,” said the extended visit “propelled me to learn more Mandarin and do a master’s [degree] in international relations focused on China.”

‘Bad Nightmare’

McCuaig-Johnston said the shutdown of the Xidan Democracy Wall movement was a prelude to the CCP’s response to the student protests on Tiananmen Square from April to June 1989.“As many as a million people gathered in Tiananmen Square, and millions others participated in shadow protests in 400 cities across the country, calling for democracy. And just like the Xidan wall, the leadership permitted and even encouraged it—until the day they didn’t,” she said.

“Sending in the tanks on the Friday and Saturday was a shock to many people in the West. And it was said that even more people were killed in the streets of Beijing that night than had died in the square.”

However, the “bad nightmare” of what became known as the Tiananmen Square massacre did not deter Prime Minister Jean Chrétien from wanting to increase trade with China when he took office in 1993, McCuaig-Johnston said.

“He was explicit that human rights and trade discussions should not be mixed,” she noted, adding that although Chrétien initiated a bilateral dialogue on human rights at the same time, the Chinese side wasn’t receptive and the dialogue was terminated nine years later.

McCuaig-Johnston said successive prime ministers, including Paul Martin, Stephen Harper, and Justin Trudeau, also met with no success when they tried discussing human rights issues with Beijing.

Surveillance

While noting that what galvanized her to become a vocal critic of the CCP was the arbitrary detention of Kovrig and Spavor, McCuaig-Johnston said that by that time she already had concerns about human rights in China on a number of other fronts.These included Chinese surveillance technology companies, including ones engaged in partnerships with Canadian researchers; the incarceration of one million Uyghurs; militarization of the islands in the South China Sea; and military threats to Taiwan.

She said she was in Shanghai when Kovrig and Spavor were arrested and her locked suitcases in her hotel room were unlocked and searched.

“I mentioned the Michaels’ detentions to a Chinese executive with whom I was meeting. He said, ‘Oh yes, China has a list of 100 Canadians that [it] can pick up and interrogate at any time,’” she said.

“When I returned home, two other Canadians mentioned the list, and one said I might be on it for my work on joint ventures.”

She decided to speak out, doing her first interview ever with the media.

“Since I was speaking out about the detentions there were a lot of other things that I thought deserved the spotlight shone on them, particularly in my wheelhouse of China’s technology development,” she said.

“For example, these Chinese surveillance technology companies are a huge human rights concern being used against the Uyghurs, Tibetans, and in general population control.”

She added that China has moved into senior ranks in international standards organizations to ensure its technologies can be sold globally, including the technology platform of BGI Genomics, which provides genomic sequencing and related services to customers in over 100 countries.

“China’s BGI is collecting genetic data from Canadians and sending it to China to be stored in China’s huge database,” she said.

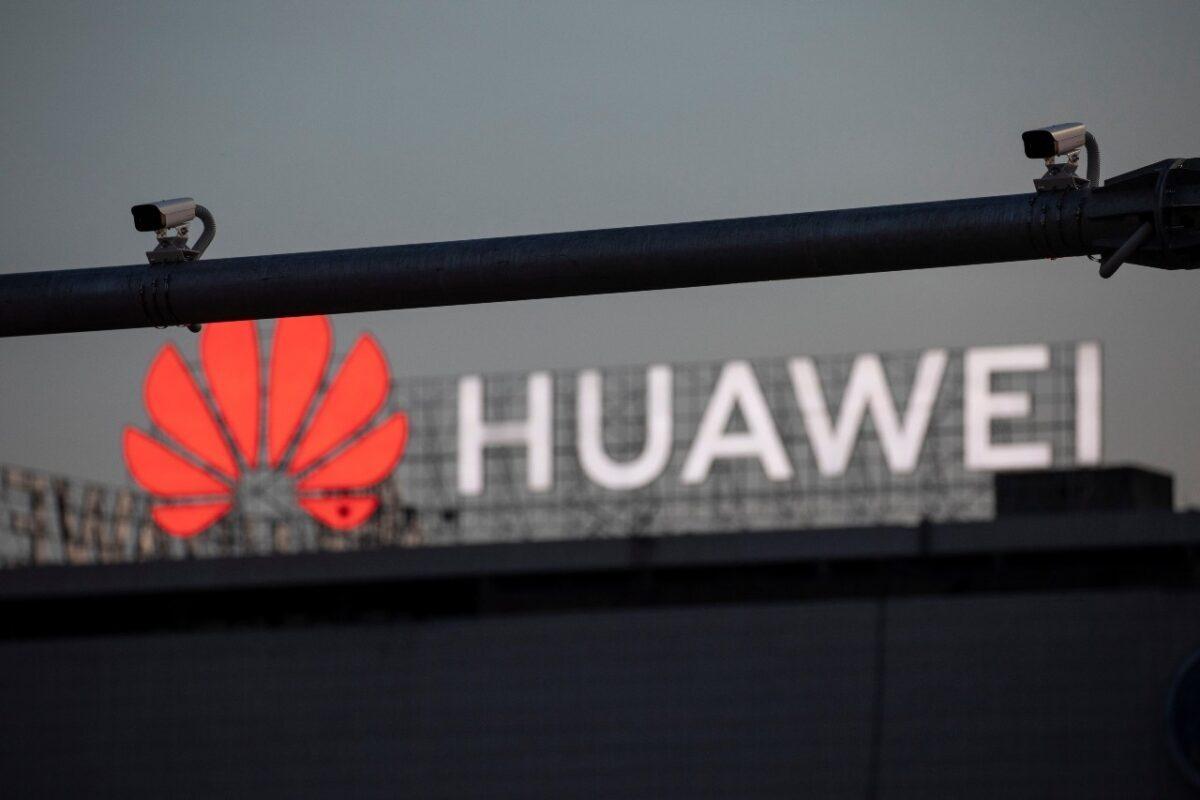

McCuaig-Johnston said that while she welcomes the federal government’s recent ban of Huawei Technologies from Canada’s 5G network, she’s worried that the uninstalling of its technology will take too long.

“I’m concerned that Telus has been installing Huawei 5G hardware and software for the past two years, and now has been given another two years before it has to be taken out of their systems by June 2024,” she said.

‘Untold Horrors’

McCuaig-Johnston says it’s important for Chinese officials to “realize that we are all watching every one of these developments closely.”She recounted that during her last trip to China in December 2018, she had dinner with a senior CCP official who was a longtime acquaintance and raised concerns about the Uyghurs who had died in the so-called re-education camps. She is a member of the Uyghur Rights Advocacy Project policy adviser team.

“His reply was, ‘People die everywhere all the time.’ To which I replied, ‘Not healthy young people,’ for which he just gave a blank stare.”

Still, McCuaig-Johnston says that “those who are in touch with Chinese officials must raise these issues as often as they can.”

She said that if she ever returns to China, she would focus on the 1.8 million Uyghur and Tibetan children who have been put in re-education camps “where their language and culture are being drummed out of them.”

“They are learning [CCP leader] Xi Jinping thought and they are not receiving adequate food or clothing. Each one is a little child experiencing untold horrors and wondering every day why their parents are not coming to rescue them. That is what the Xi regime is doing to its own people.” she said.

McCuaig-Johnston is also a member of the Canada U.S. Commission on China, an advisory board member with the Canada China Forum, and a board member of the Canadian International Council’s National Capital Branch.

Friends Read Free