Since the current regime leader Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China has launched many a prestige project, like the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB). Ostensibly they are for economic development in the region, however most experts agree that this is just one reason for the massive Chinese investment in trade and infrastructure abroad.

“China has a deliberate strategy to translate its economic capabilities... all of the tools it has in its disposal, to translate that into political influence,” said Evan Medeiros, head of Asia-Pacific research at Eurasia Group, at the Foreign Policy Association’s World Leadership Forum in New York Sept. 28.

For this reason China founded the AIIB alongside 56 member-states and an initial capital investment of $100 billion. In 2016, the bank pledged $1.7 billion to nine projects, mostly in Central Asia.

Medeiros says the strategy of investment creates dependency without confrontation. “There is a coercive but non-confrontational element,” he said.

Examples of using economics to pursue political ends included an export ban on rare-earth exports to Japan in 2010, and restriction of agricultural imports from the Philippines in 2012. The goal of the Chinese is to further their geopolitical agenda centered around territorial disputes in the South China Sea and to expand their navy reach to the Indian Ocean.

Poor Track Record

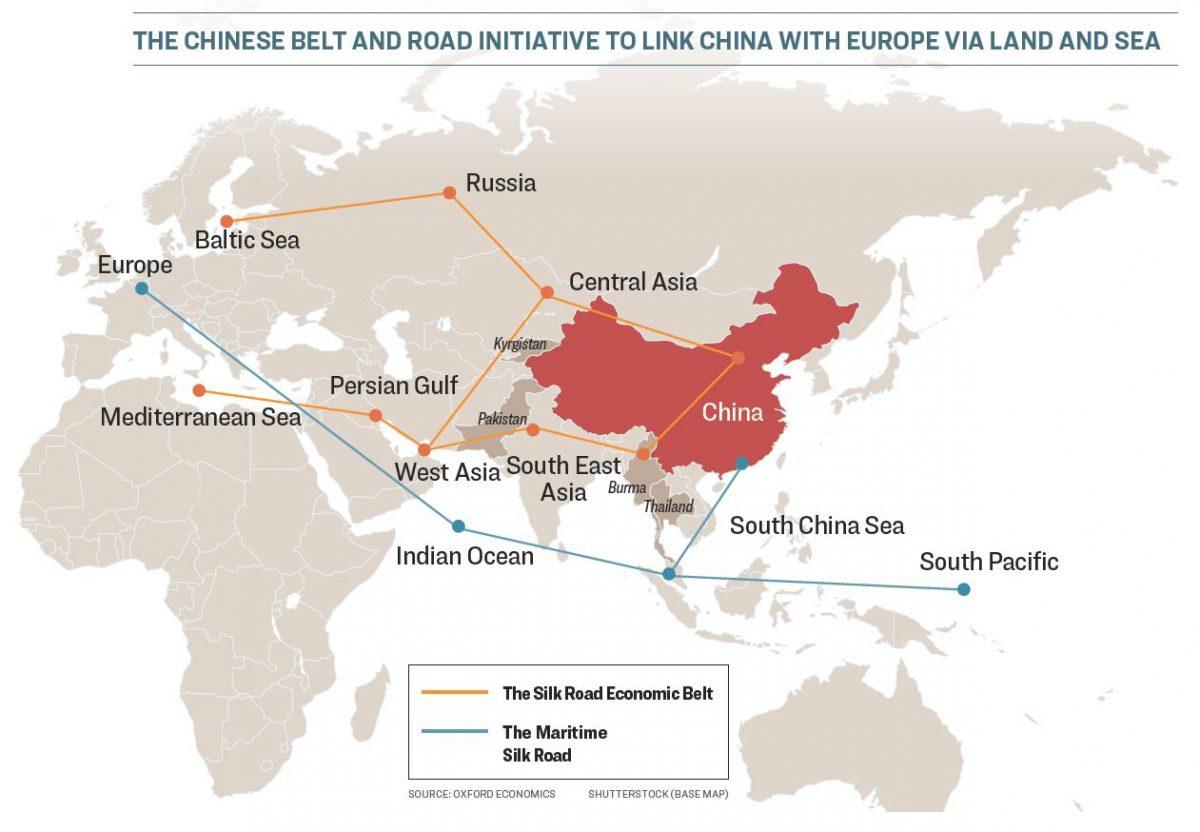

However, with huge investment projects like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the AIIB, the biggest pressure point is to exclude countries from being recipients of Chinese investment.The BRI is by far the biggest project and promises to advance central Asian countries’ economies. It was announced by Xi Jinping in 2013. Although estimates vary, China has called for up to $5 trillion in infrastructure investments over the next five years in the 65 countries along land-locked and maritime trade routes. Ports in Sri Lanka, railways in Thailand, and massive roads and power plants in Pakistan are just a few examples of the planned investments.

The idea, at first, sounds good: Plow trillions of dollars into infrastructure projects in the undeveloped region that is most of central Asia, and trade will start to bloom, economies will prosper, and peace will reign. However, the experts on the panel at the World Leadership Forum think there is a significant risk involved.

“When you look at what the BRI has accomplished after four years, it’s much less than what people would have imagined. You read the headlines of what the Chinese pledged... Roughly a third of that gets realized,” said Elizabeth Economy, C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and Director for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Although not officially part of the Belt and Road Initiative, the $3.6 billion Myitsone Dam project in Burma is an example of a Chinese infrastructure project in a very poor country that hasn’t gone as planned. Construction has been suspended for six years, as both countries could not agree on how to proceed.

Another not-so successful model for a Chinese development initiative is Venezuela, said Daniel Rosen, founding partner of the Rhodium Group (RHG). China lent $65 billion to the troubled nation in South America, “the vast bulk of which will never be recovered. It has even undermined its development process,” Rosen said.

He also points to China’s poor track record in getting returns on its investments. “This is not the first time China has put out a great plan that didn’t achieve its objectives.”

Friends Read Free