On the surface, China is talking the reform talk. But is it also walking the walk? There are many examples to demonstrate it isn’t. The most recent one is a directive from the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) to not cut off lending to troubled companies and to evergreen bad loans. This first reported by The Chinese National Business Daily on Aug. 4.

“A Notice About How the Creditor Committees at Banks and Financial Institutes Should Do Their Jobs” tells banks to ”act together and not ‘randomly stop giving or pulling loans.’ These institutes should either provide new loans after taking back the old ones or provide a loan extension, to ‘fully help companies to solve their problems,’” the National Business Daily writes.

“It’s big news. A couple of weeks ago they were threatening Liaoning Province to cut off all lending to them if they didn’t tighten loan standards,” said Christopher Balding, a professor of economics at Peking University in Shenzen. “This is a pretty significant turn-around for them to do and it indicates how significant the problem is.”

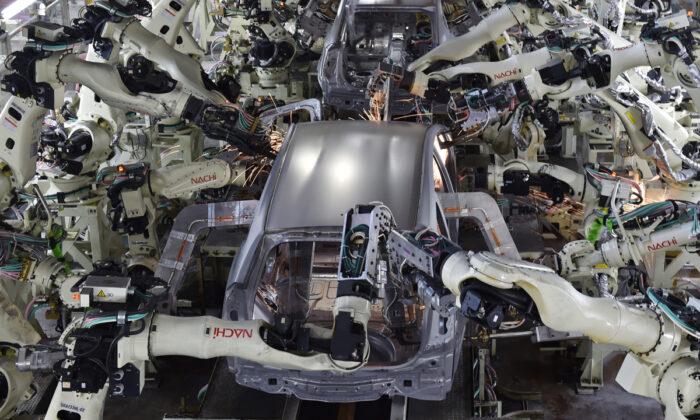

The official reform narrative is espoused in this Xinhua piece which claims China has to reform because there is no Plan B. “Supply-side structural reform is also advancing as the country moves to address issues like industrial overcapacity, a large inventory of unsold homes and unprofitable ‘zombie companies.’” Clearly resolving the bad debt of zombie companies is not high on the priority list.

Goldman Sachs complained in a recent note to clients that companies can default on payments and often nothing happens. The investment bank notes that companies like Sichuan Coal default on payments of interest and principal for weeks or months and then maybe pay creditors later. The company in question defaulted on 1 billion yuan ($150 million) worth of commercial paper in June but made full payments later during the summer, a somewhat arbitrary process.

Another case is Dongbei Special Steel, which missed at least five payments on $6 billion of debt since the beginning of the year, but has done nothing to resolve the problem. This is why creditors wrote an angry letter to the local government to help resolve the issue.

According to Goldman Sachs, Dongbei was the reason Liaoning Province came under pressure:

“A bondholders meeting took place ... with bondholders requesting that the [regulators] halt fundraising by the Liaoning provincial government and the enterprises in Liaoning province, and that institutional investors should stop purchasing bonds issued by the Liaoning government and the enterprises in Liaoning province. According to news reports, this demand stems from disappointment in progress by the provincial government in resolving Dongbei Special Steel’s debt problems, with a lack of information and no clear resolution plan.”

“Going forward, we do expect this trend to continue, with more defaults given our expectation of slower growth in the second half, and continued uncertainties on how these defaults are resolved,” Goldman Sachs wrote.

With the blessing of the regulator, Goldman’s prediction is probably correct. The investment bank notes that 11 out of 18 high-profile defaults have not been resolved since the first official default of a Chinese company by Chaori Solar in 2014.

Christopher Balding thinks the directive shows how serious the debt situation has gotten. “This does indicate that there is a relatively significant pressure on the system and people aren’t making their payments. ‘Look, don’t rock the boat and push people into default.’ To say it so publicly or bluntly is amazing.”

The notice did include a modifier stating that the companies to be supported “must have a good outlook in terms of either their products or services and have restructuring values,” and that the “the development of the companies should be in line with the macro-economic policy, industrial policy and financial supporting policy of the country.” How serious banks will take this modifier is open to debate.

Overall bankruptcies in China have surged 52.5 percent in the first quarter of 2016 compared to a year earlier with 1028 cases being reported by the Supreme People’s Court. Most cases that are resolved involve small companies with few employees. The small firms are liquidated rather than restructured, according to the Financial Times. As we have seen there is another measure applied to larger companies, much to the dismay of Goldman Sachs:

“A clearer debt resolution process ... would help to pave the way for more defaults, which in our view are needed if policymakers are to deliver on structural reforms.” If they want to deliver.

Follow Valentin on Twitter: @vxschmid

Friends Read Free