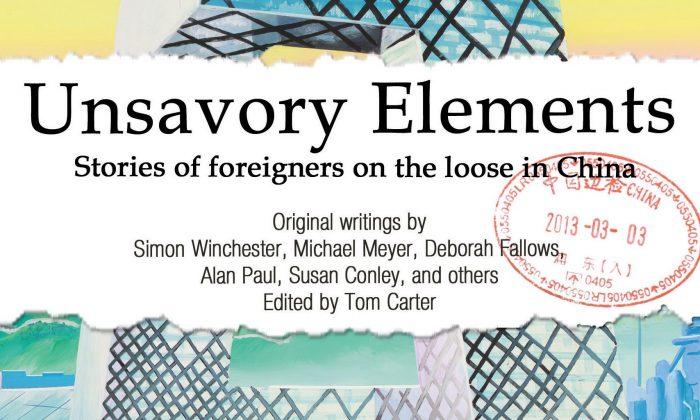

Tom Carter, a photographer and editor based in Shanghai, last year published a collection of two dozen reminiscences by foreigners to China about their time in the country. Contributors include well-known writers in the small world of expatriates who, at least at one time, called China home.

There is no theme, and little prescription seems to have been given by Carter to his contributors: each entry is a dozen or so pages, and consists of a vignette about life in China. Inevitably what is brought out is the ubiquitous difference between the reality the writers are used to in their own countries (usually America) and that which now confronts them.

All of the representations are direct and unvarnished. Michael Levy, whose essay appears first in the book, was given the opportunity of forging English language school applications for $1,000 each.

“I stopped breathing. I had eighteen students total. Each of their essays would take no more than a few hours,” Levy writes. “My sweating got worse as my nerves mixed with the heat. I took a sip of coffee, swallowed, and suspiciously scanned the conspicuous consumers of Starbucks.” Many of the other essays are equally enjoyable to read.

In Levy’s case, he turned down the offer because of a funny thing called his conscience. This seemed incomprehensible to Mr. Mao, an admissions broker for rich Chinese parents who wanted their children to attend private American boarding schools. The pervasive cynicism of his environment allowed Mr. Mao to believe that the offer was not cheating, but merely giving the kids a chance. For a lot of money.

Matthew Polly, another contributor, paid to get beaten by Shaolin Monks (it was called “training.”) To make money, he struck upon the idea of selling t-shirts hand-painted by them. “One of the first things I had learned during my stay,” Polly writes, “was that the Chinese love to negotiate. They love it so much that even after an agreement is reached they’ll often reopen negotiations just so they can do it all over again.”

He was outfoxed by a local businessman in a t-shirt deal, despite sharing foreign cigarettes and getting the man drunk on harsh Chinese spirits. Polly had tried to become as Chinese as the Chinese, but he would never really be Chinese, as all foreigners in China eventually realize.

Enamored and Stifled

Matt Muller, a former marine, went to China to teach English: of course, high jinks ensued. Kay Bratt writes about how her children learnt Chinese by playing with other kids. Dan Washburn ate pig’s ears and got drunk on corn wine. Kaitlin Solimine lived with a Chinese family in a tiny apartment. Rudy Kong got stuck in an ice hockey fight. Nury Vittachi got robbed. And so on.

All of the foreigners show the ways in which they personally became enamored with China and the Chinese and their language.

They also reveal the contours of contemporary Chinese society, shaped at it has been in the image of the Chinese Communist Party that has ruled China since 1949. There is not a lot of dwelling on politics or the Party itself, but there is a stifling sense throughout the book that something is askew in the way China works, and the political system that underpins it always seems to be lurking somewhere in the background.

Graham Earnshaw, for example, started a company that ran a website called Shanghai-ed, and he explored other publishing ventures. “Operating in the interstices of communist China society was at once exhilarating and uncertain,” he writes. “There were no rules. Or rather, there was only one rule: that nothing is allowed. But the corollary, which reveals the true genius of China’s love of the grey—in contrast to the black and white of the West—is that everything is possible. Nothing is allowed but everything is possible.” (Whether “genius” is the right word for this peculiarly modern contradiction is another matter.)

“It’s just a matter of finding the right way to explain what you’re doing,” he adds. His newspaper was shut down after a state-run publication (whose advertising dollars he was presumably taking) got wind of it. Years later he had another publication business, which had become highly profitable, stolen by other official predators. So it goes, in China.

The two dozen tales document a stunning variety of experiences, and paint a portrait of China that is at once repulsive and fascinating. There is a sameness to the “fish out of water” sense that comes through in every piece, but at the same time, the experience of China as the Other has a respectable pedigree.

As Simon Leys, the peerless Belgian sinologist, was fond of quoting André Malraux, the French novelist writing nearly a century ago: “China is the other pole of the human experience.” “Unsavory Elements” shows that it remains so to this day.

Friends Read Free