The killing of 43 student teachers in Mexico has alerted the world to the country’s deteriorating human rights record. While the U.S. and E.U. governments have expressed concern, others—including the U.K.—have remained silent.

The students were abducted in September, while they were protesting in the town of Iguala, Guerrero. The mayor, Jose Luis Abarca, is reported to have ordered police to abduct the students, to prevent them disrupting a speech his wife was giving. A local gang has admitted to the killings and said the police handed the students to them.

It took 24 hours for the state governor Angel Aguirre to issue an arrest warrant over the abductions and by that time, the mayor, his wife and the local police chief had fled the town. Only last week, Abarca and his wife were finally tracked down.

The federal government now says it believes the 43 students were killed, though it has been unable to extract DNA from the remains found. The gang had burned the bodies for 15 hours in a municipal rubbish dump, before dismembering and disposing of them in a river.

The news has led to a wave of protests. As author George Grayson put it: “There is not enough whitewash in the world to cover this.”

The Iguala massacre followed another shameful event—the extra-judicial execution of at least 12 gang members by Mexican soldiers in Tlatlaya, near Mexico City. State and federal prosecutors investigated the scene but declared there was no cause for concern. The case only came to light in August because Human Rights Watch pursued it. Subsequently, the Mexican Army passed sentence on seven soldiers, including an officer. No action has been taken against the civil prosecutors.

The two cases are very different, but in both, Mexican officials at all levels were implicated in sins of commission and omission, with horrific results.

The Broader Picture

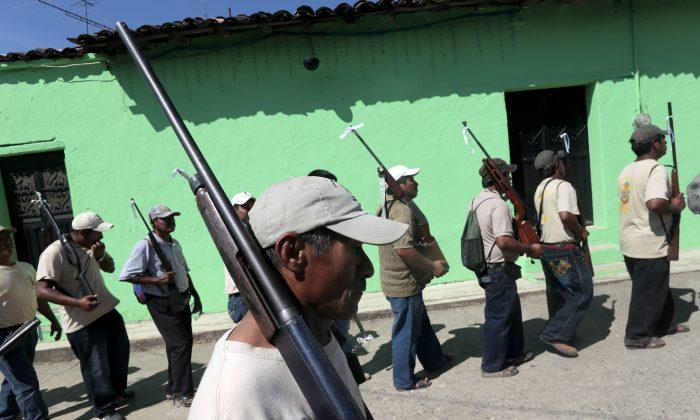

Iguala and Tlatlaya are by no means anomalies. In the neighboring state of Michoacan, thousands of vigilantes armed themselves in January to fight criminal gangs who were in league with state authorities. The federal government is still struggling to contain the uprising. And the U.S. government has warned citizens against travelling to the northern state of Tamaulipas—although it continues to dump illegal immigrants there.

And beyond these flashpoints, it is estimated that 77 percent of municipal governments are controlled by organized crime gangs. These criminal groups control local police, as well as some state and even federal officers. They abduct and murder at will. This was my own experience in the state of Jalisco. Gang activity there gets little media coverage, but hundreds were being abducted while the authorities made excuses for their inaction.

Many Mexicans have little—if any—protection from gangs, or indeed from the police and army, who are implicated in torture and enforced disappearances. The numbers are spine-chilling. It has been estimated that as many as 100,000 people have been killed in the country’s drug war since 2006.

Business as Usual

Human rights groups hope that the world’s attention will push Mexico to make a priority of restoring human rights in the country. Mexico is especially sensitive at the moment because its oil reserves, nationalized in 1938, are about to be opened up to foreign investment. With bids being welcomed from January, Mexico’s Energy secretary Pedro Joaquin Coldwell has boldly predicted that the massacres would not deter investors. Yet the government is clearly worried.

And it has reason to worry. As John Scimgeour, director of the University of Aberdeen Energy Institute, suggests, energy companies may be put off by the negative publicity associated with human rights abuses. They will also be “much more reluctant” to operate in the country if they cannot guarantee the safety of their personnel. Another concern will be whether the government can avoid corruption in the industry.

Companies often look to their governments for cues on how to proceed and the Iguala case has certainly raised red flags in some quarters. The White House has expressed concern and the European Parliament voted 495 to 86 to call on the Mexican government to find the 43 missing students before their deaths were confirmed.

Yet other governments have refrained from comment. The U.K. government is a case in point. 2015 will be the year of “Mexico in the U.K., U.K. in Mexico,” heralded by Prince Charles’s recent visit. Despite or possibly because of this, the U.K. has remained silent on the recent events.

In the past, the U.K. has argued that human rights abuses are often best addressed not by condemnation but by engagement—for example, through U.K. companies investing in skills. In recent months, the government has been briefing businesses about the opportunities on offer in Mexico’s energy sector.

U.K. Trade & Investment official John Tominey takes an upbeat view. Tominey recognizes that “Mexico has problems regarding its complex social and ethnic makeup which complicates the issue of tackling corruption and improving on its human rights record.” The perception of corruption in Mexico is, he admits, “an impediment to business.”

But he adds that British businesses are currently achieving great successes within the energy industry in Mexico and “we do not expect much to change due to the recent and very unfortunate events in Iguala.” Referring to the wider package of sociopolitical reforms, Tominey predicts: “The resignation of the governor of Guerrero has to be taken as a positive move away from the culture of impunity. I expect this situation to cause the government significant discomfort but not to derail the recent progress made through the reform agenda.”

Time will tell whether the U.K. approach is the best model for promoting human rights in countries whose governments are seeking foreign business. For now, it is unlikely to satisfy either the Mexican protesters or global human rights groups, desperate for an end to the carnage.

Trevor Stack is a senior lecturer in Hispanic studies, and director of the Centre for Citizenship, Civil Society and Rule of Law at the University of Aberdeen in the U.K. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Friends Read Free