The arrival of European settlement in Australia was a time of great upheaval, dispossession and displacement for the Indigenous Aboriginal population. Since the late 1800s a succession of laws allowed the removal of Aboriginal children from their families into government agencies and church missions. These children are known as the Stolen Generation.

Over the last six years, Sydney based artist Asher Milgate has spent countless hours “yarning” with some of the surviving elders, and elders-in-waiting, about life at the Nanmina Mission, the longest operating Aboriginal mission reserve in Central New South Wales.

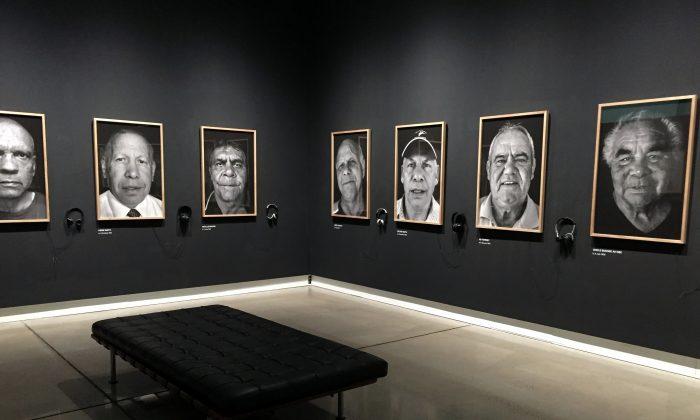

Using a series of black and white photographic portraits combined with interactive audio recordings, Mr Milgate captures the soulful experiences of 18 elders from the Bunjang people of the Wiradjuri nation, who grew up in Nanima Mission. Milgate’s project Survivors sheds light on how life under European settlement effected Aboriginal people.

Sharing with him some of their most intimate past and present life stories, Survivors serves as an oral record of the often missing Indigenous part of Australian history. The hardships associated with displacement are revealed through the stories told in this powerful exhibition.

Aboriginal elder Aunty Joyce recalls her childhood, when speaking Aboriginal in school was considered “bad language and they would be caned for it.” She also talked of the friendship and bonds, which formed between the Aboriginal and early Chinese communities.

“On the Bell River, the Chinese would have a garden market and would lend money, and you would pay them back by working in the garden. They were a part of our survival.”

Elder Herbie Smith, remembers the inherent fear of police who became a stigma among the older Aboriginal generation, because the police were responsible for removing children from their families.

“They'd get the orders come through from the welfare board … it was the police that had to enforce those orders. So people saw them as baddies.”

Aunty Ethel Kelly describes the trauma and injustices that were forced upon her during her childhood.

“As a child, losing a lot of my family members in the Stolen Generation and having my grandmother remove me so that I wasn’t part of it … you know, just being told to get off the Mission and not having the choice to live out there on the Common anymore … We were told we had to move, and one family member was told, as a baby, if you weren’t removed from the Mission that the baby would be taken away,” she said in an interview on SBS.

Ms Kelly believes this exhibition will help families reconnect, “They got knocked down, but they got back up again. They still know where their families are, and they are coming back home. Families are going to connect through this, they are going to see the photos, so it’s putting a lot of history into place.”

Mr Milgate described the works as, “chilling, uplifting and evocative.”

Mr Milgate hopes that through this exhibition people, especially younger generations, will “learn what it was like for Aboriginal people growing up,” and in the process challenge misconceptions about Aboriginal culture.

“At present there is little or no empathy in the wider Australian community. A basic failure to understand that the Aboriginal communities were forced to assimilate and that their language and cultural practices have been taken away, with many still struggling to come to terms with living in a white man’s world,” he said in a phone interview.

Mr Milgate would like his exhibition to give voice to the wider Indigenous Australian community.

The exhibition will run until May 10, 2015 at the Western Plains Cultural Centre, 76 Wingewarra Street, Dubbo, NSW.

For more information on the exhibition please visit www.survivors.net.au

Friends Read Free