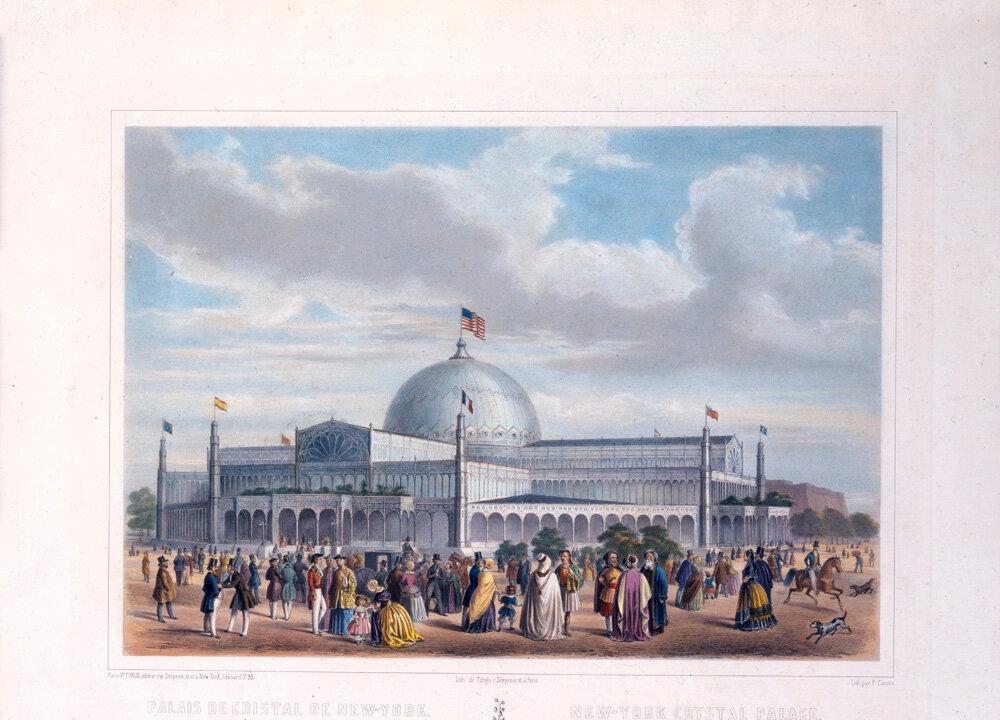

It often takes an extensive lapse of time to discover what has been gained through progress. By this same token, and perhaps even more importantly, time unveils what we have lost. The New-York Historical Society (NYHS) recently pulled back the veil on some of the great monuments, works of art, and places regrettably lost to the march of change, progress, and expansion. This exhibit called “Lost New York” opened on April 19 and will continue through Sept. 29, 2024.

According to Wendy Nalani E. Ikemoto, NYHS vice president and chief curator, she had been considering creating this exhibit for some time, but it was not until the Society received two pieces of New York City-related art that she was able to do so.