The infected blood scandal “could largely have been avoided” according a report that has been published after a public inquiry which lasted for six years and cost millions of pounds.

The chairman of the inquiry, Sir Brian Langstaff, said a “pervasive” cover-up had been perpetrated to hide the truth and he criticised a “litany of failures” by successive governments since the early 1970s when Edward Heath was prime minister.

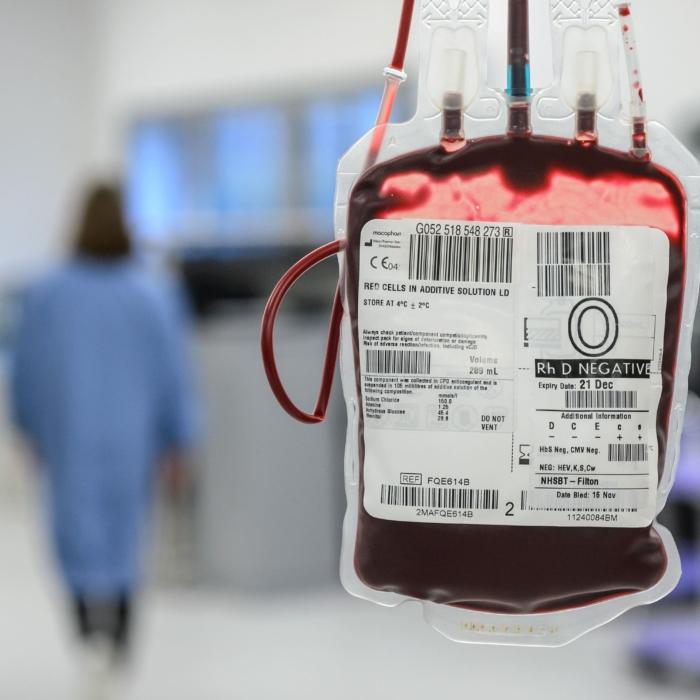

Tens of thousands of people in the UK were infected with HIV, hepatitis, and other deadly viruses after being given contaminated blood and factor VIII products between the 1970s and the early 1990s.

Around 3,000 people died—with the number climbing every week—and many others have been left with life-long health complications.

He pointed out that when Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was chancellor in 2020 he failed to respond to two letters from the then-paymaster general, Penny Mordaunt, which urged the Treasury to begin work on compensation.

Sir Brian said, “People whose lives were torn apart by the wrongs done at individual, collective and systemic levels, and by the way in which successive governments responded to what happened, still have no idea as to the shape, extent or form of any compensation scheme.”

Mr. Sunak is expected to issue an apology later for the failures of successive governments.

On Tuesday the government is expected to outline the details of a compensation scheme, which is expected to cost the public purse £10 billion.

Most of the contaminated blood was imported from the United States, where donors—who were paid for their blood—included drug addicts and prison inmates.

Blood used for transfusions was not screened for HIV until 1986 and testing for hepatitis C did not begin until 1991.

‘Worst Treatment Disaster in the History of the NHS’

He said, “Lord [Robert] Winston famously called these events ‘the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS’. I have to report that it could largely, though not entirely, have been avoided,” added Sir Brian.Among the mistakes that were made was a decision in 1983 not to ban the import of commercial blood products.

Those who received the infected blood included people who were undergoing surgery or suffered problems during childbirth.

Sir Brian said, “Lives, dreams, friendships, families, finances were destroyed.”

Up to 6,000 people with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders were infected with hepatitis.

Only 250 of the 1,250 who were co-infected with both hepatitis and HIV are still alive today.

Parents ‘Felt a Lot of Guilt’

Martin Reid, 44, from Aberdeenshire, was infected as a child and has been left with lasting effects from the virus, including anxiety and depression.He said: “My parents were both distraught about it. They felt a lot of guilt about it, I guess as any parent would.”

“I consider myself one of the lucky ones that wasn’t infected with HIV, like so many other people were, and I have lived to the age where I have been able to have a family, I am still here. So I do feel like one of the lucky ones,” added Mr. Reid.

Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham has called the infected blood scandal a “criminal cover-up on an industrial scale.”

As health secretary between June 2009 and May 2010, Mr. Burnham told an infected person there was no evidence people were knowingly given contaminated blood.

He later discovered what he had said was untrue and he has called for the introduction of a so-called Hillsborough law, which would prevent civil servants, health officials, or police officers from giving anybody, especially an elected official, “information they know to be false.”

In April 2017, in his final speech in Parliament, Mr. Burnham called for a public inquiry and three months later the then-Prime Minister Theresa May agreed to set it up.

It held its first official hearing in April 2019 and has heard testimony from 374 people, as well as taking 5,000 witness statements and reviewing more than 100,000 documents.

Sir Brian said he found Department of Health documents that revealed the truth about the scandal had been “marked” for destruction in 1993.

Cover-Up Was ‘Subtle,’ ‘Pervasive,’ and ‘Chilling’

“Not in the sense of a handful of people plotting in an orchestrated conspiracy to mislead, but in a way that was more subtle, more pervasive and more chilling in its implications. In this way there has been a hiding of much of the truth,” it added.He said repeated claims from successive governments that blood screening had been introduced at the earliest opportunity were “untrue.”

Sir Brian said both Labour and Conservative governments failed to take action, partly to save face and partly to avoid the huge expense involved.

He said as the scale of the scandal became clear, decision-making was slow and governments preserved a “doctor knows best” attitude in a misguided attempt to protect patients from distress.

At a press conference after delivering his report, Sir Brian was applauded as he said, “I fully expect the government to make an apology.”

“To be meaningful, though, that apology must explain what the apology is for, it should recognise and acknowledge not just the suffering, but the fact that the suffering was the result of errors, wrongs done, and delays incurred,” he added.

Sir Brian said, “It should provide vindication to those who have waited for that for so long, and it should be accompanied by action.”

Scotland’s public health minister Jenni Minto welcomed the report and said, “On behalf of the Scottish Government, I reiterate our sincere apology to those who have been infected or affected by NHS blood or blood products.”