Commentary

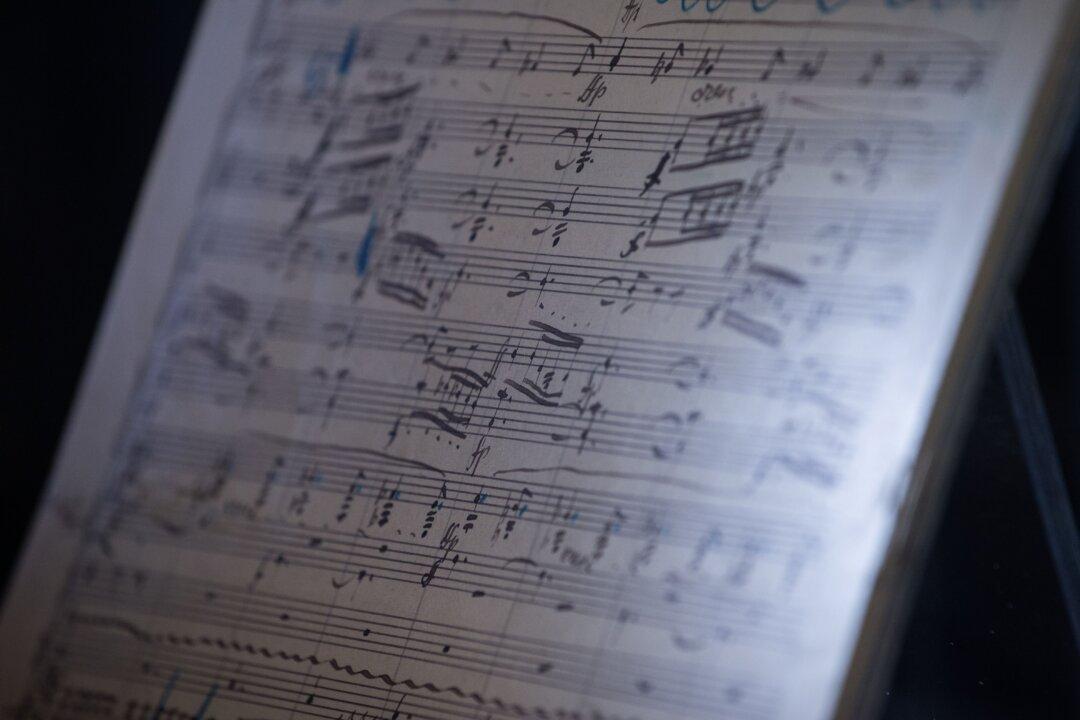

In the darkest days of lockdown, as the sun went down on the world, and stayed that way for so long, finding suitable music choices was not easy. My usual attachment to Mahler symphonies had to be shelved. Within these symphonies, you find the whole human experience and eternity as a bonus. It was enough to be watching such earth-shattering events in the world without hearing a soundtrack. So Mahler was simply impossible to hear for me personally.